Laos - LA - LAO - LAO - East and Southeast Asia

Last updated: January 21, 2026

Laos Images

Laos Factbook Data

Diplomatic representation from the US

chief of mission: Ambassador Heather VARIAVA (since 5 February 2024)

embassy: Ban Somvang Tai, Thadeua Road, Km 9, Hatsayfong District, Vientiane

mailing address: 4350 Vientiane Place, Washington DC 20521-4350

telephone: [856] 21-48-7000

FAX: [856] 21-48-7040

email address and website:

CONSLAO@state.gov

https://la.usembassy.gov/

embassy: Ban Somvang Tai, Thadeua Road, Km 9, Hatsayfong District, Vientiane

mailing address: 4350 Vientiane Place, Washington DC 20521-4350

telephone: [856] 21-48-7000

FAX: [856] 21-48-7040

email address and website:

CONSLAO@state.gov

https://la.usembassy.gov/

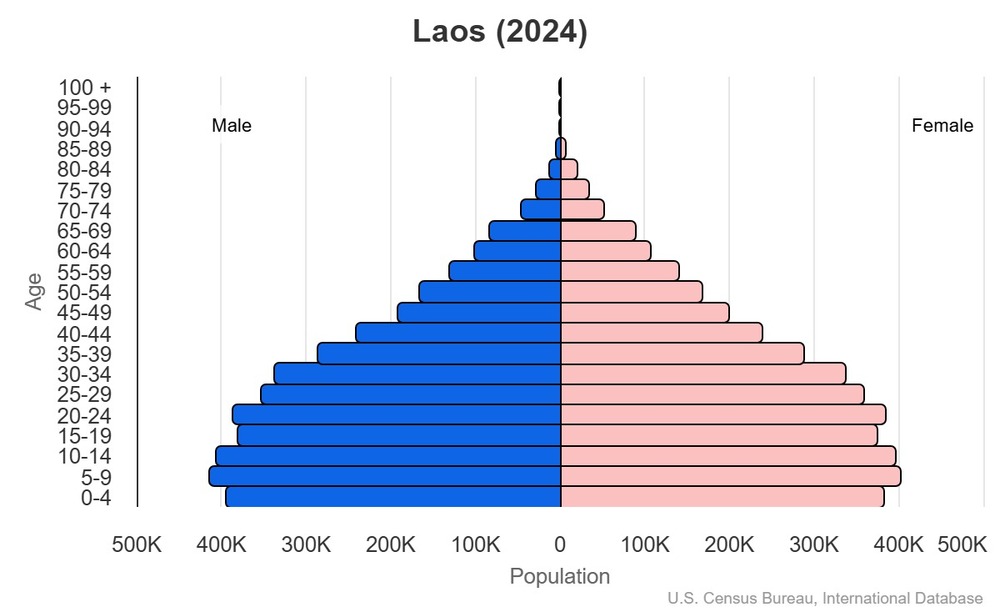

Age structure

0-14 years: 30.1% (male 1,214,429/female 1,181,845)

15-64 years: 65% (male 2,573,668/female 2,599,957)

65 years and over: 4.8% (2024 est.) (male 178,223/female 205,434)

15-64 years: 65% (male 2,573,668/female 2,599,957)

65 years and over: 4.8% (2024 est.) (male 178,223/female 205,434)

This is the population pyramid for Laos. A population pyramid illustrates the age and sex structure of a country's population and may provide insights about political and social stability, as well as economic development. The population is distributed along the horizontal axis, with males shown on the left and females on the right. The male and female populations are broken down into 5-year age groups represented as horizontal bars along the vertical axis, with the youngest age groups at the bottom and the oldest at the top. The shape of the population pyramid gradually evolves over time based on fertility, mortality, and international migration trends.

For additional information, please see the entry for Population pyramid on the Definitions and Notes page.

For additional information, please see the entry for Population pyramid on the Definitions and Notes page.

Geographic coordinates

18 00 N, 105 00 E

Sex ratio

at birth: 1.04 male(s)/female

0-14 years: 1.03 male(s)/female

15-64 years: 0.99 male(s)/female

65 years and over: 0.87 male(s)/female

total population: 1 male(s)/female (2024 est.)

0-14 years: 1.03 male(s)/female

15-64 years: 0.99 male(s)/female

65 years and over: 0.87 male(s)/female

total population: 1 male(s)/female (2024 est.)

Natural hazards

floods, droughts

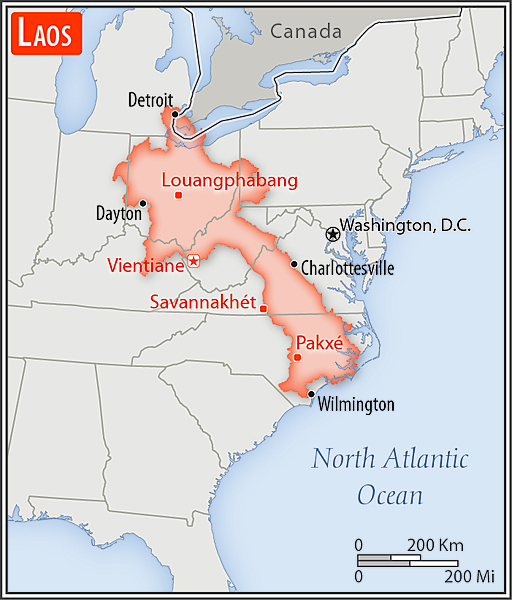

Area - comparative

about twice the size of Pennsylvania; slightly larger than Utah

about twice the size of Pennsylvania; slightly larger than Utah

Military service age and obligation

18 years of age for voluntary military service; mandatory military service for men 18-35 with a minimum 18-month service obligation (2025)

Background

Modern-day Laos has its roots in the ancient Lao kingdom of Lan Xang, established in the 14th century under King FA NGUM. For 300 years, Lan Xang had influence reaching into present-day Cambodia and Thailand, as well as over all of what is now Laos. After centuries of gradual decline, Laos came under the domination of Siam (Thailand) from the late 18th century until the late 19th century, when it became part of French Indochina. The Franco-Siamese Treaty of 1907 defined the current Lao border with Thailand. Following more than 15 years of civil war, the communist Pathet Lao took control of the government in 1975, ending a six-century-old monarchy and instituting a one party--the Lao People's Revolutionary Party--communist state. A gradual, limited return to private enterprise and the liberalization of foreign investment laws began in the late 1980s. Laos became a member of ASEAN in 1997 and the WTO in 2013.

In the 2010s, the country benefited from direct foreign investment, particularly in the natural resource and industry sectors. Construction of a number of large hydropower dams and expanding mining activities have also boosted the economy. Laos has retained its official commitment to communism and maintains close ties with its two communist neighbors, Vietnam and China, both of which continue to exert substantial political and economic influence on the country. China, for example, provided 70% of the funding for a $5.9 billion, 400-km railway line between the Chinese border and the capital Vientiane, which opened for operations in 2021. Laos financed the remaining 30% with loans from China. At the same time, Laos has expanded its economic reliance on the West and other Asian countries, such as Japan, Malaysia, Singapore, Taiwan, and Thailand. Nevertheless, despite steady economic growth for more than a decade, it remains one of Asia's poorest countries.

In the 2010s, the country benefited from direct foreign investment, particularly in the natural resource and industry sectors. Construction of a number of large hydropower dams and expanding mining activities have also boosted the economy. Laos has retained its official commitment to communism and maintains close ties with its two communist neighbors, Vietnam and China, both of which continue to exert substantial political and economic influence on the country. China, for example, provided 70% of the funding for a $5.9 billion, 400-km railway line between the Chinese border and the capital Vientiane, which opened for operations in 2021. Laos financed the remaining 30% with loans from China. At the same time, Laos has expanded its economic reliance on the West and other Asian countries, such as Japan, Malaysia, Singapore, Taiwan, and Thailand. Nevertheless, despite steady economic growth for more than a decade, it remains one of Asia's poorest countries.

Environmental issues

unexploded ordnance; deforestation; soil erosion; loss of biodiversity; water pollution; limited access to potable water

International environmental agreements

party to: Biodiversity, Climate Change, Climate Change-Kyoto Protocol, Climate Change-Paris Agreement, Comprehensive Nuclear Test Ban, Desertification, Endangered Species, Environmental Modification, Hazardous Wastes, Law of the Sea, Nuclear Test Ban, Ozone Layer Protection, Wetlands, Whaling

signed, but not ratified: none of the selected agreements

signed, but not ratified: none of the selected agreements

Military expenditures

0.2% of GDP (2019 est.)

0.2% of GDP (2018 est.)

0.2% of GDP (2017 est.)

0.2% of GDP (2016 est.)

0.2% of GDP (2015 est.)

0.2% of GDP (2018 est.)

0.2% of GDP (2017 est.)

0.2% of GDP (2016 est.)

0.2% of GDP (2015 est.)

Population below poverty line

18.3% (2018 est.)

note: % of population with income below national poverty line

note: % of population with income below national poverty line

Household income or consumption by percentage share

lowest 10%: 3% (2018 est.)

highest 10%: 31.2% (2018 est.)

note: % share of income accruing to lowest and highest 10% of population

highest 10%: 31.2% (2018 est.)

note: % share of income accruing to lowest and highest 10% of population

Exports - commodities

electricity, fertilizers, gold, garments, paper (2023)

note: top five export commodities based on value in dollars

note: top five export commodities based on value in dollars

Exports - partners

China 39%, Thailand 34%, Australia 4%, USA 4%, Cambodia 2% (2023)

note: top five export partners based on percentage share of exports

note: top five export partners based on percentage share of exports

Administrative divisions

17 provinces (khoueng, singular and plural) and 1 prefecture* (kampheng nakhon); Attapu, Bokeo, Bolikhamxay, Champasak, Houaphanh, Khammouan, Louangnamtha, Louangphabang (Luang Prabang), Oudomxai, Phongsali, Salavan, Savannakhet, Viangchan (Vientiane)*, Viangchan, Xaignabouli, Xaisomboun, Xekong, Xiangkhouang

Agricultural products

cassava, root vegetables, rice, sugarcane, vegetables, bananas, maize, rubber, coffee, watermelons (2023)

note: top ten agricultural products based on tonnage

note: top ten agricultural products based on tonnage

Military and security forces

Lao People's Armed Forces (LPAF; aka Lao People's Army): Lao People's Army (LPA, includes Riverine Force), Lao People's Air Force (LPAF); Self-Defense Militia Forces (2025)

note: the Ministry of Public Security maintains internal security and is responsible for law enforcement; it oversees local, traffic, immigration, and security police, village police auxiliaries, and other armed police units

note: the Ministry of Public Security maintains internal security and is responsible for law enforcement; it oversees local, traffic, immigration, and security police, village police auxiliaries, and other armed police units

Budget

revenues: $2.288 billion (2022 est.)

expenditures: $2.259 billion (2022 est.)

note: central government revenues and expenses (excluding grants/extrabudgetary units/social security funds) converted to US dollars at average official exchange rate for year indicated

expenditures: $2.259 billion (2022 est.)

note: central government revenues and expenses (excluding grants/extrabudgetary units/social security funds) converted to US dollars at average official exchange rate for year indicated

Capital

name: Vientiane (Viangchan)

geographic coordinates: 17 58 N, 102 36 E

time difference: UTC+7 (12 hours ahead of Washington, DC, during Standard Time)

etymology: the name Viangchan means "city of sandalwood" in Laotian; the standard spelling reflects French influence

geographic coordinates: 17 58 N, 102 36 E

time difference: UTC+7 (12 hours ahead of Washington, DC, during Standard Time)

etymology: the name Viangchan means "city of sandalwood" in Laotian; the standard spelling reflects French influence

Imports - commodities

refined petroleum, cars, raw sugar, plastic products, trucks (2023)

note: top five import commodities based on value in dollars

note: top five import commodities based on value in dollars

Climate

tropical monsoon; rainy season (May to November); dry season (December to April)

Coastline

0 km (landlocked)

Constitution

history: previous 1947 (pre-independence); latest promulgated 13-15 August 1991

amendment process: proposed by the National Assembly; passage requires at least two-thirds majority vote of the Assembly membership and promulgation by the president of the republic

amendment process: proposed by the National Assembly; passage requires at least two-thirds majority vote of the Assembly membership and promulgation by the president of the republic

Exchange rates

kips (LAK) per US dollar -

Exchange rates:

17,688.874 (2023 est.)

14,035.227 (2022 est.)

9,697.916 (2021 est.)

9,045.788 (2020 est.)

8,679.409 (2019 est.)

Exchange rates:

17,688.874 (2023 est.)

14,035.227 (2022 est.)

9,697.916 (2021 est.)

9,045.788 (2020 est.)

8,679.409 (2019 est.)

Flag

description: three horizontal bands of red (top), blue (double-width), and red, with a large white disk centered in the blue band

meaning: red stands for the blood shed for liberation, and blue for the Mekong River and prosperity; the white disk represents the full moon over the Mekong River and the unity of the people under the Lao People's Revolutionary Party, as well as the country's bright future

meaning: red stands for the blood shed for liberation, and blue for the Mekong River and prosperity; the white disk represents the full moon over the Mekong River and the unity of the people under the Lao People's Revolutionary Party, as well as the country's bright future

Illicit drugs

USG identification:

major illicit drug-producing and/or drug-transit country (2025)

major illicit drug-producing and/or drug-transit country (2025)

Independence

19 July 1949 (from France); 22 October 1953 (Franco-Lao Treaty recognizes full independence)

Industries

mining (copper, tin, gold, gypsum); timber, electric power, agricultural processing, rubber, construction, garments, cement, tourism

Judicial branch

highest court(s): People's Supreme Court (consists of the court president and organized into criminal, civil, administrative, commercial, family, and juvenile chambers, each with a vice president and several judges)

judge selection and term of office: president of People's Supreme Court appointed by the National Assembly upon the recommendation of the president of the republic for a 5-year term; vice presidents of the People's Supreme Court appointed by the president of the republic upon the recommendation of the National Assembly; appointment of chamber judges NA; tenure of court vice presidents and chamber judges NA

subordinate courts: appellate courts; provincial, municipal, district, and military courts

judge selection and term of office: president of People's Supreme Court appointed by the National Assembly upon the recommendation of the president of the republic for a 5-year term; vice presidents of the People's Supreme Court appointed by the president of the republic upon the recommendation of the National Assembly; appointment of chamber judges NA; tenure of court vice presidents and chamber judges NA

subordinate courts: appellate courts; provincial, municipal, district, and military courts

Land boundaries

total: 5,274 km

border countries (5): Burma 238 km; Cambodia 555 km; China 475 km; Thailand 1,845 km; Vietnam 2,161 km

border countries (5): Burma 238 km; Cambodia 555 km; China 475 km; Thailand 1,845 km; Vietnam 2,161 km

Land use

agricultural land: 9.9% (2023 est.)

arable land: 5.3% (2023 est.)

permanent crops: 1.7% (2023 est.)

permanent pasture: 2.9% (2023 est.)

forest: 56.8% (2023 est.)

other: 33.3% (2023 est.)

arable land: 5.3% (2023 est.)

permanent crops: 1.7% (2023 est.)

permanent pasture: 2.9% (2023 est.)

forest: 56.8% (2023 est.)

other: 33.3% (2023 est.)

Legal system

civil law system similar in form to the French system

Legislative branch

legislature name: National Assembly (Sapha Heng Xat)

legislative structure: unicameral

number of seats: 164 (all directly elected)

electoral system: plurality/majority

scope of elections: full renewal

term in office: 5 years

most recent election date: 2/21/2021

parties elected and seats per party: Lao People's Revolutionary Party (LPRP) (158); Other (6)

percentage of women in chamber: 22%

expected date of next election: February 2026

legislative structure: unicameral

number of seats: 164 (all directly elected)

electoral system: plurality/majority

scope of elections: full renewal

term in office: 5 years

most recent election date: 2/21/2021

parties elected and seats per party: Lao People's Revolutionary Party (LPRP) (158); Other (6)

percentage of women in chamber: 22%

expected date of next election: February 2026

Literacy

total population: 75.6% (2023 est.)

male: 85.1% (2023 est.)

female: 66.7% (2023 est.)

male: 85.1% (2023 est.)

female: 66.7% (2023 est.)

Maritime claims

none (landlocked)

International organization participation

ADB, ARF, ASEAN, CP, EAS, FAO, G-77, IAEA, IBRD, ICAO, ICRM, IDA, IFAD, IFC, IFRCS, ILO, IMF, Interpol, IOC, IPU, ISO (subscriber), ITU, MIGA, NAM, OIF, OPCW, PCA, UN, UNCTAD, UNESCO, UNIDO, UNWTO, UPU, WCO, WFTU (NGOs), WHO, WIPO, WMO, WTO

National holiday

Republic Day (National Day), 2 December (1975)

Nationality

noun: Lao(s) or Laotian(s)

adjective: Lao or Laotian

adjective: Lao or Laotian

Natural resources

timber, hydropower, gypsum, tin, gold, gemstones

Geography - note

landlocked; most of the country is mountainous and thickly forested; the Mekong River forms a large part of the western boundary with Thailand

Economic overview

lower middle-income, socialist Southeast Asian economy; one of the fastest growing economies; declining but still high poverty; natural resource rich; new anticorruption efforts; already high and growing public debt; service sector hit hard by COVID-19

Political parties

Lao People's Revolutionary Party or LPRP

note: other parties proscribed

note: other parties proscribed

Suffrage

18 years of age; universal

Terrain

mostly rugged mountains; some plains and plateaus

Government type

communist party-led state

Military - note

the LPAF’s primary missions are border and internal security, including counterinsurgency, counterterrorism, and counter-narcotics operations, as well as protecting the regime; its defense partners include Cambodia, China, Russia, and Vietnam (2025)

Country name

conventional long form: Lao People's Democratic Republic

conventional short form: Laos

local long form: Sathalanalat Paxathipatai Paxaxon Lao

local short form: Mueang Lao (unofficial)

abbreviation: Lao PDR

etymology: name means "Land of the Lao [people];" it derives from the name of the country's founder, Lao

conventional short form: Laos

local long form: Sathalanalat Paxathipatai Paxaxon Lao

local short form: Mueang Lao (unofficial)

abbreviation: Lao PDR

etymology: name means "Land of the Lao [people];" it derives from the name of the country's founder, Lao

Location

Southeastern Asia, northeast of Thailand, west of Vietnam

Map references

Southeast Asia

Irrigated land

4,410 sq km (2022)

Diplomatic representation in the US

chief of mission: Ambassador PHOUKHONG Sisoulath (since 5 September 2025)

chancery: 2222 S Street NW, Washington, DC 20008

telephone: [1] (202) 332-6416

FAX: [1] (202) 332-4923

email address and website:

embasslao@gmail.com

https://laoembassy.com/

chancery: 2222 S Street NW, Washington, DC 20008

telephone: [1] (202) 332-6416

FAX: [1] (202) 332-4923

email address and website:

embasslao@gmail.com

https://laoembassy.com/

Internet users

percent of population: 64% (2023 est.)

Internet country code

.la

GDP (official exchange rate)

$16.503 billion (2024 est.)

note: data in current dollars at official exchange rate

note: data in current dollars at official exchange rate

Trafficking in persons

tier rating: Tier 3 — Laos does not fully meet the minimum standards for the elimination of trafficking and is not making significant efforts to do so, therefore, Laos was downgraded to Tier 3; for more details, go to: https://www.state.gov/reports/2025-trafficking-in-persons-report/laos/

Total renewable water resources

333.5 billion cubic meters (2022 est.)

School life expectancy (primary to tertiary education)

total: 9 years (2023 est.)

male: 9 years (2023 est.)

female: 9 years (2023 est.)

male: 9 years (2023 est.)

female: 9 years (2023 est.)

Urbanization

urban population: 38.2% of total population (2023)

rate of urbanization: 2.99% annual rate of change (2020-25 est.)

rate of urbanization: 2.99% annual rate of change (2020-25 est.)

Broadcast media

6 TV stations operating out of Vientiane, with half state-operated and half commercial; 17 provincial stations, with nearly all programming relayed via satellite from the state-operated stations in Vientiane; multi-channel satellite and cable TV systems provide access to a wide range of foreign stations; state-controlled radio with state-operated Lao National Radio (LNR) broadcasting on 5 frequencies; transmissions of multiple international broadcasters are accessible

Drinking water source

improved:

urban: 97.1% of population (2022 est.)

rural: 78.5% of population (2022 est.)

total: 85.5% of population (2022 est.)

unimproved:

urban: 2.9% of population (2022 est.)

rural: 21.5% of population (2022 est.)

total: 14.5% of population (2022 est.)

urban: 97.1% of population (2022 est.)

rural: 78.5% of population (2022 est.)

total: 85.5% of population (2022 est.)

unimproved:

urban: 2.9% of population (2022 est.)

rural: 21.5% of population (2022 est.)

total: 14.5% of population (2022 est.)

National anthem(s)

title: "Pheng Xat Lao" (Hymn of the Lao People)

lyrics/music: SISANA Sisane/THONGDY Sounthonevichit

history: music adopted 1945, lyrics adopted 1975; the anthem's lyrics were changed after the communist revolution that overthrew the monarchy in 1975

lyrics/music: SISANA Sisane/THONGDY Sounthonevichit

history: music adopted 1945, lyrics adopted 1975; the anthem's lyrics were changed after the communist revolution that overthrew the monarchy in 1975

This is an audio of the National Anthem for Laos. The national anthem is generally a patriotic musical composition - usually in the form of a song or hymn of praise - that evokes and eulogizes the history, traditions, or struggles of a nation or its people. National anthems can be officially recognized as a national song by a country's constitution or by an enacted law, or simply by tradition. Although most anthems contain lyrics, some do not.

Major urban areas - population

721,000 VIENTIANE (capital) (2023)

International law organization participation

has not submitted an ICJ jurisdiction declaration; non-party state to the ICCt

Physician density

0.33 physicians/1,000 population (2022)

Hospital bed density

1.3 beds/1,000 population (2021 est.)

National symbol(s)

elephant

GDP - composition, by end use

household consumption: 65.7% (2016 est.)

government consumption: 14% (2016 est.)

investment in fixed capital: 29% (2016 est.)

investment in inventories: 0% (2016 est.)

exports of goods and services: 33.2% (2016 est.)

imports of goods and services: -41.9% (2016 est.)

note: figures may not total 100% due to rounding or gaps in data collection

government consumption: 14% (2016 est.)

investment in fixed capital: 29% (2016 est.)

investment in inventories: 0% (2016 est.)

exports of goods and services: 33.2% (2016 est.)

imports of goods and services: -41.9% (2016 est.)

note: figures may not total 100% due to rounding or gaps in data collection

Citizenship

citizenship by birth: no

citizenship by descent only: at least one parent must be a citizen of Laos

dual citizenship recognized: no

residency requirement for naturalization: 10 years

citizenship by descent only: at least one parent must be a citizen of Laos

dual citizenship recognized: no

residency requirement for naturalization: 10 years

Population distribution

most densely populated area is in and around the capital city of Vientiane; large communities are primarily found along the Mekong River along the southwestern border; overall density is considered one of the lowest in Southeast Asia

Electricity access

electrification - total population: 100% (2022 est.)

Civil aircraft registration country code prefix

RDPL

Sanitation facility access

improved:

urban: 100% of population (2022 est.)

rural: 72% of population (2022 est.)

total: 82.5% of population (2022 est.)

unimproved:

urban: 0% of population (2022 est.)

rural: 28% of population (2022 est.)

total: 17.5% of population (2022 est.)

urban: 100% of population (2022 est.)

rural: 72% of population (2022 est.)

total: 82.5% of population (2022 est.)

unimproved:

urban: 0% of population (2022 est.)

rural: 28% of population (2022 est.)

total: 17.5% of population (2022 est.)

Ethnic groups

Lao 53.2%, Khmou 11%, Hmong 9.2%, Phouthay 3.4%, Tai 3.1%, Makong 2.5%, Katong 2.2%, Lue 2%, Akha 1.8%, other 11.6% (2015 est.)

note: the Laos Government officially recognizes 49 ethnic groups, but the total number of ethnic groups is estimated to be well over 200

note: the Laos Government officially recognizes 49 ethnic groups, but the total number of ethnic groups is estimated to be well over 200

Religions

Buddhist 64.7%, Christian 1.7%, none 31.4%, other/not stated 2.1% (2015 est.)

Languages

Lao (official), French, English, various ethnic languages

major-language sample(s):

ແຫລ່ງທີ່ຂາດບໍ່ໄດ້ສຳລັບຂໍ້ມູນຕົ້ນຕໍ່” (Lao)

The World Factbook, the indispensable source for basic information.

major-language sample(s):

ແຫລ່ງທີ່ຂາດບໍ່ໄດ້ສຳລັບຂໍ້ມູນຕົ້ນຕໍ່” (Lao)

The World Factbook, the indispensable source for basic information.

Lao audio sample

Imports - partners

Thailand 58%, China 36%, Japan 1%, Singapore 1%, Germany 1% (2023)

note: top five import partners based on percentage share of imports

note: top five import partners based on percentage share of imports

Refugees and internally displaced persons

IDPs: 1,274 (2024 est.)

Elevation

highest point: Phu Bia 2,817 m

lowest point: Mekong River 70 m

mean elevation: 710 m

lowest point: Mekong River 70 m

mean elevation: 710 m

Health expenditure

2.7% of GDP (2021)

4.3% of national budget (2022 est.)

4.3% of national budget (2022 est.)

Military and security service personnel strengths

information limited and varied; estimated 30,000 active Armed Forces; estimated 100,000 Self-Defense Militia Forces (2025)

Military equipment inventories and acquisitions

the LPAF is armed with Chinese, Russian, and Soviet-era equipment and weapons (2025)

Total water withdrawal

municipal: 130 million cubic meters (2022 est.)

industrial: 170 million cubic meters (2022 est.)

agricultural: 7.05 billion cubic meters (2022 est.)

industrial: 170 million cubic meters (2022 est.)

agricultural: 7.05 billion cubic meters (2022 est.)

Waste and recycling

municipal solid waste generated annually: 351,900 tons (2024 est.)

percent of municipal solid waste recycled: 15.1% (2022 est.)

percent of municipal solid waste recycled: 15.1% (2022 est.)

Average household expenditures

on food: 50.5% of household expenditures (2023 est.)

on alcohol and tobacco: 7.8% of household expenditures (2023 est.)

on alcohol and tobacco: 7.8% of household expenditures (2023 est.)

Major watersheds (area sq km)

Pacific Ocean drainage: Mekong (805,604 sq km)

Major rivers (by length in km)

Mènam Khong (Mekong) (shared with China [s], Burma, Thailand, Cambodia, and Vietnam [m]) - 4,350 km

note: [s] after country name indicates river source; [m] after country name indicates river mouth

note: [s] after country name indicates river source; [m] after country name indicates river mouth

National heritage

total World Heritage Sites: 3 (all cultural)

selected World Heritage Site locales: Town of Luangphrabang; Vat Phou and Associated Ancient Settlements; Megalithic Jar Sites in Xiengkhuang - Plain of Jars

selected World Heritage Site locales: Town of Luangphrabang; Vat Phou and Associated Ancient Settlements; Megalithic Jar Sites in Xiengkhuang - Plain of Jars

Child marriage

women married by age 15: 7.1% (2017)

women married by age 18: 32.7% (2017)

men married by age 18: 10.8% (2017)

women married by age 18: 32.7% (2017)

men married by age 18: 10.8% (2017)

Coal

production: 16.629 million metric tons (2023 est.)

consumption: 15.944 million metric tons (2023 est.)

exports: 1.065 million metric tons (2023 est.)

imports: 22,000 metric tons (2023 est.)

proven reserves: 62 million metric tons (2023 est.)

consumption: 15.944 million metric tons (2023 est.)

exports: 1.065 million metric tons (2023 est.)

imports: 22,000 metric tons (2023 est.)

proven reserves: 62 million metric tons (2023 est.)

Electricity generation sources

fossil fuels: 23.3% of total installed capacity (2023 est.)

solar: 0.2% of total installed capacity (2023 est.)

hydroelectricity: 76.5% of total installed capacity (2023 est.)

biomass and waste: 0.1% of total installed capacity (2023 est.)

solar: 0.2% of total installed capacity (2023 est.)

hydroelectricity: 76.5% of total installed capacity (2023 est.)

biomass and waste: 0.1% of total installed capacity (2023 est.)

Petroleum

refined petroleum consumption: 25,000 bbl/day (2023 est.)

Gross reproduction rate

1.07 (2025 est.)

Currently married women (ages 15-49)

61.6% (2017 est.)

Remittances

1.8% of GDP (2023 est.)

1.5% of GDP (2022 est.)

1.2% of GDP (2021 est.)

note: personal transfers and compensation between resident and non-resident individuals/households/entities

1.5% of GDP (2022 est.)

1.2% of GDP (2021 est.)

note: personal transfers and compensation between resident and non-resident individuals/households/entities

Railways

total: 422 km (2023)

standard gauge: 422 km (2023) 1.435-m gauge (422 km overhead electrification)

standard gauge: 422 km (2023) 1.435-m gauge (422 km overhead electrification)

National color(s)

red, white, blue

Particulate matter emissions

20.5 micrograms per cubic meter (2019 est.)

Labor force

3.585 million (2024 est.)

note: number of people ages 15 or older who are employed or seeking work

note: number of people ages 15 or older who are employed or seeking work

Youth unemployment rate (ages 15-24)

total: 2.2% (2024 est.)

male: 2.4% (2024 est.)

female: 2.1% (2024 est.)

note: % of labor force ages 15-24 seeking employment

male: 2.4% (2024 est.)

female: 2.1% (2024 est.)

note: % of labor force ages 15-24 seeking employment

Net migration rate

-0.93 migrant(s)/1,000 population (2025 est.)

Median age

total: 25.8 years (2025 est.)

male: 25 years

female: 25.7 years

male: 25 years

female: 25.7 years

Debt - external

$9.619 billion (2023 est.)

note: present value of external debt in current US dollars

note: present value of external debt in current US dollars

Maternal mortality ratio

112 deaths/100,000 live births (2023 est.)

Reserves of foreign exchange and gold

$1.77 billion (2023 est.)

$1.576 billion (2022 est.)

$1.951 billion (2021 est.)

note: holdings of gold (year-end prices)/foreign exchange/special drawing rights in current dollars

$1.576 billion (2022 est.)

$1.951 billion (2021 est.)

note: holdings of gold (year-end prices)/foreign exchange/special drawing rights in current dollars

Total fertility rate

2.19 children born/woman (2025 est.)

Unemployment rate

1.3% (2024 est.)

1.2% (2023 est.)

1.3% (2022 est.)

note: % of labor force seeking employment

1.2% (2023 est.)

1.3% (2022 est.)

note: % of labor force seeking employment

Carbon dioxide emissions

23.412 million metric tonnes of CO2 (2023 est.)

from coal and metallurgical coke: 19.652 million metric tonnes of CO2 (2023 est.)

from petroleum and other liquids: 3.76 million metric tonnes of CO2 (2023 est.)

from coal and metallurgical coke: 19.652 million metric tonnes of CO2 (2023 est.)

from petroleum and other liquids: 3.76 million metric tonnes of CO2 (2023 est.)

Area

total : 236,800 sq km

land: 230,800 sq km

water: 6,000 sq km

land: 230,800 sq km

water: 6,000 sq km

Taxes and other revenues

12.1% (of GDP) (2022 est.)

note: central government tax revenue as a % of GDP

note: central government tax revenue as a % of GDP

Real GDP (purchasing power parity)

$66.905 billion (2024 est.)

$64.173 billion (2023 est.)

$61.856 billion (2022 est.)

note: data in 2021 dollars

$64.173 billion (2023 est.)

$61.856 billion (2022 est.)

note: data in 2021 dollars

Airports

20 (2025)

Infant mortality rate

total: 34.2 deaths/1,000 live births (2025 est.)

male: 39.1 deaths/1,000 live births

female: 31.6 deaths/1,000 live births

male: 39.1 deaths/1,000 live births

female: 31.6 deaths/1,000 live births

Gini Index coefficient - distribution of family income

38.8 (2018 est.)

note: index (0-100) of income distribution; higher values represent greater inequality

note: index (0-100) of income distribution; higher values represent greater inequality

Inflation rate (consumer prices)

23.1% (2024 est.)

31.2% (2023 est.)

23% (2022 est.)

note: annual % change based on consumer prices

31.2% (2023 est.)

23% (2022 est.)

note: annual % change based on consumer prices

Current account balance

$404.523 million (2023 est.)

-$458.754 million (2022 est.)

$431.636 million (2021 est.)

note: balance of payments - net trade and primary/secondary income in current dollars

-$458.754 million (2022 est.)

$431.636 million (2021 est.)

note: balance of payments - net trade and primary/secondary income in current dollars

Real GDP per capita

$8,600 (2024 est.)

$8,400 (2023 est.)

$8,200 (2022 est.)

note: data in 2021 dollars

$8,400 (2023 est.)

$8,200 (2022 est.)

note: data in 2021 dollars

Broadband - fixed subscriptions

total: 183,000 (2022 est.)

subscriptions per 100 inhabitants: 2 (2022 est.)

subscriptions per 100 inhabitants: 2 (2022 est.)

Tobacco use

total: 24.1% (2025 est.)

male: 41% (2025 est.)

female: 7.2% (2025 est.)

male: 41% (2025 est.)

female: 7.2% (2025 est.)

Obesity - adult prevalence rate

5.3% (2016)

Energy consumption per capita

34.463 million Btu/person (2023 est.)

Death rate

6.07 deaths/1,000 population (2025 est.)

Birth rate

19.22 births/1,000 population (2025 est.)

Electricity

installed generating capacity: 12.738 million kW (2023 est.)

consumption: 12.803 billion kWh (2023 est.)

exports: 38 billion kWh (2023 est.)

imports: 955.095 million kWh (2023 est.)

transmission/distribution losses: 2.447 billion kWh (2023 est.)

consumption: 12.803 billion kWh (2023 est.)

exports: 38 billion kWh (2023 est.)

imports: 955.095 million kWh (2023 est.)

transmission/distribution losses: 2.447 billion kWh (2023 est.)

Merchant marine

total: 1 (2023)

by type: general cargo 1

by type: general cargo 1

Children under the age of 5 years underweight

24.3% (2023 est.)

Imports

$8.596 billion (2023 est.)

$7.983 billion (2022 est.)

$6.527 billion (2021 est.)

note: balance of payments - imports of goods and services in current dollars

$7.983 billion (2022 est.)

$6.527 billion (2021 est.)

note: balance of payments - imports of goods and services in current dollars

Exports

$9.698 billion (2023 est.)

$8.604 billion (2022 est.)

$7.82 billion (2021 est.)

note: balance of payments - exports of goods and services in current dollars

$8.604 billion (2022 est.)

$7.82 billion (2021 est.)

note: balance of payments - exports of goods and services in current dollars

Alcohol consumption per capita

total: 8.15 liters of pure alcohol (2019 est.)

beer: 3.62 liters of pure alcohol (2019 est.)

wine: 0.07 liters of pure alcohol (2019 est.)

spirits: 4.46 liters of pure alcohol (2019 est.)

other alcohols: 0 liters of pure alcohol (2019 est.)

beer: 3.62 liters of pure alcohol (2019 est.)

wine: 0.07 liters of pure alcohol (2019 est.)

spirits: 4.46 liters of pure alcohol (2019 est.)

other alcohols: 0 liters of pure alcohol (2019 est.)

Life expectancy at birth

total population: 69 years (2024 est.)

male: 67.4 years

female: 70.7 years

male: 67.4 years

female: 70.7 years

Real GDP growth rate

4.3% (2024 est.)

3.7% (2023 est.)

2.7% (2022 est.)

note: annual GDP % growth based on constant local currency

3.7% (2023 est.)

2.7% (2022 est.)

note: annual GDP % growth based on constant local currency

Industrial production growth rate

3.9% (2024 est.)

note: annual % change in industrial value added based on constant local currency

note: annual % change in industrial value added based on constant local currency

GDP - composition, by sector of origin

agriculture: 16.8% (2024 est.)

industry: 29% (2024 est.)

services: 43.5% (2024 est.)

note: figures may not total 100% due to non-allocated consumption not captured in sector-reported data

industry: 29% (2024 est.)

services: 43.5% (2024 est.)

note: figures may not total 100% due to non-allocated consumption not captured in sector-reported data

Education expenditure

1.2% of GDP (2023 est.)

8.2% national budget (2024 est.)

8.2% national budget (2024 est.)

Population growth rate

1.22% (2025 est.)

Executive branch

chief of state: President THONGLOUN Sisoulith (since 22 March 2021)

head of government: Prime Minister SONEXAY (also spelled SONXAI) Siphandon (since 30 December 2022)

cabinet: Council of Ministers appointed by the president and approved by the National Assembly

election/appointment process: president and vice president indirectly elected by the National Assembly for a 5-year term (no term limits); prime minister nominated by the president, elected by the National Assembly for a 5-year term

most recent election date: 22 March 2021

election results:

2021: THONGLOUN Sisoulith (LPRP) elected president; National Assembly vote - 161-1; PHANKHAM Viphavanh (LPRP) elected prime minister; National Assembly vote - 158-3

2016: BOUNNHANG Vorachit (LPRP) elected president; percent of National Assembly vote - NA; THONGLOUN Sisoulith (LPRP) elected prime minister; percent of National Assembly vote - NA

expected date of next election: March 2026

note: President THONGLOUN Sisoulith is also general secretary of the Lao People's Revolutionary Party

head of government: Prime Minister SONEXAY (also spelled SONXAI) Siphandon (since 30 December 2022)

cabinet: Council of Ministers appointed by the president and approved by the National Assembly

election/appointment process: president and vice president indirectly elected by the National Assembly for a 5-year term (no term limits); prime minister nominated by the president, elected by the National Assembly for a 5-year term

most recent election date: 22 March 2021

election results:

2021: THONGLOUN Sisoulith (LPRP) elected president; National Assembly vote - 161-1; PHANKHAM Viphavanh (LPRP) elected prime minister; National Assembly vote - 158-3

2016: BOUNNHANG Vorachit (LPRP) elected president; percent of National Assembly vote - NA; THONGLOUN Sisoulith (LPRP) elected prime minister; percent of National Assembly vote - NA

expected date of next election: March 2026

note: President THONGLOUN Sisoulith is also general secretary of the Lao People's Revolutionary Party

Telephones - mobile cellular

total subscriptions: 4.96 million (2023 est.)

subscriptions per 100 inhabitants: 65 (2023 est.)

subscriptions per 100 inhabitants: 65 (2023 est.)

Dependency ratios

total dependency ratio: 52.9 (2025 est.)

youth dependency ratio: 45.3 (2025 est.)

elderly dependency ratio: 7.6 (2025 est.)

potential support ratio: 13.1 (2025 est.)

youth dependency ratio: 45.3 (2025 est.)

elderly dependency ratio: 7.6 (2025 est.)

potential support ratio: 13.1 (2025 est.)

Population

total: 8,052,913 (2025 est.)

male: 4,016,077

female: 4,036,836

male: 4,016,077

female: 4,036,836

Telephones - fixed lines

total subscriptions: 1.23 million (2023 est.)

subscriptions per 100 inhabitants: 16 (2023 est.)

subscriptions per 100 inhabitants: 16 (2023 est.)