Burundi - BI - BDI - BDI - Africa

Last updated: January 05, 2026

Burundi Images

Burundi Factbook Data

Diplomatic representation from the US

chief of mission: Ambassador Lisa PETERSON (since 27 June 2024)

embassy: No 50 Avenue Des Etats-Unis, 110-01-02, Bujumbura

mailing address: 2100 Bujumbura Place, Washington DC 20521-2100

telephone: [257] 22-207-000

FAX: [257] 22-222-926

email address and website:

BujumburaC@state.gov

https://bi.usembassy.gov/

embassy: No 50 Avenue Des Etats-Unis, 110-01-02, Bujumbura

mailing address: 2100 Bujumbura Place, Washington DC 20521-2100

telephone: [257] 22-207-000

FAX: [257] 22-222-926

email address and website:

BujumburaC@state.gov

https://bi.usembassy.gov/

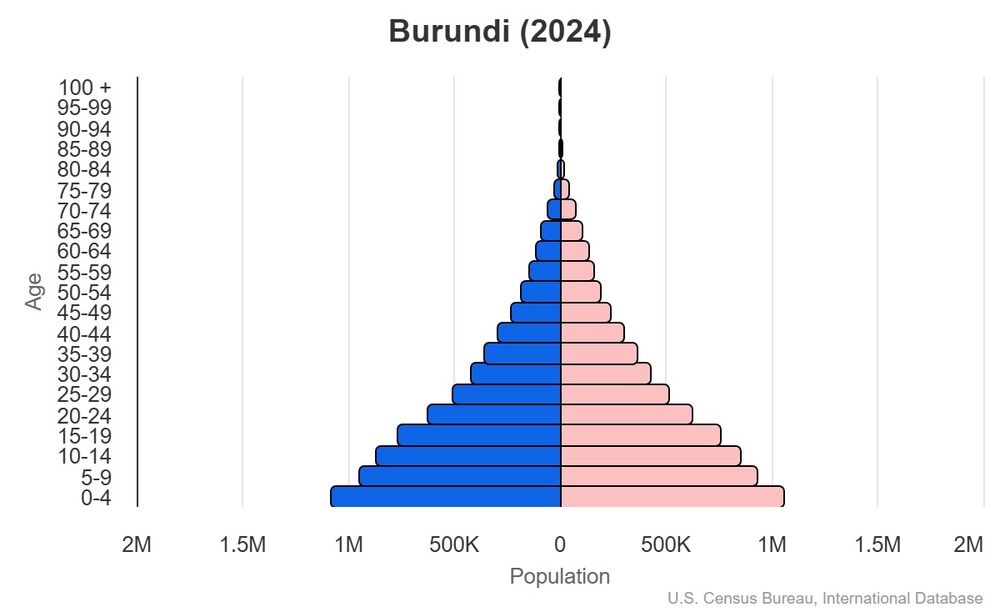

Age structure

0-14 years: 42.3% (male 2,895,275/female 2,848,286)

15-64 years: 54.4% (male 3,662,688/female 3,727,022)

65 years and over: 3.4% (2024 est.) (male 197,493/female 259,338)

15-64 years: 54.4% (male 3,662,688/female 3,727,022)

65 years and over: 3.4% (2024 est.) (male 197,493/female 259,338)

This is the population pyramid for Burundi. A population pyramid illustrates the age and sex structure of a country's population and may provide insights about political and social stability, as well as economic development. The population is distributed along the horizontal axis, with males shown on the left and females on the right. The male and female populations are broken down into 5-year age groups represented as horizontal bars along the vertical axis, with the youngest age groups at the bottom and the oldest at the top. The shape of the population pyramid gradually evolves over time based on fertility, mortality, and international migration trends.

For additional information, please see the entry for Population pyramid on the Definitions and Notes page.

For additional information, please see the entry for Population pyramid on the Definitions and Notes page.

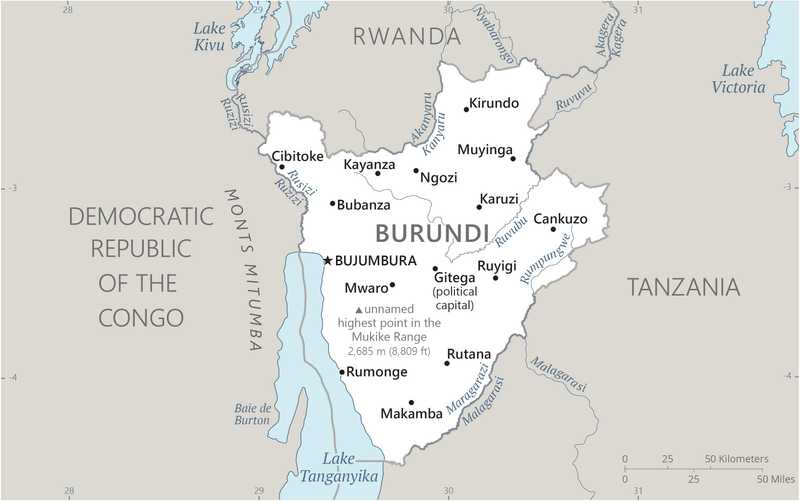

Geographic coordinates

3 30 S, 30 00 E

Sex ratio

at birth: 1.03 male(s)/female

0-14 years: 1.02 male(s)/female

15-64 years: 0.98 male(s)/female

65 years and over: 0.76 male(s)/female

total population: 0.99 male(s)/female (2024 est.)

0-14 years: 1.02 male(s)/female

15-64 years: 0.98 male(s)/female

65 years and over: 0.76 male(s)/female

total population: 0.99 male(s)/female (2024 est.)

Natural hazards

flooding; landslides; drought

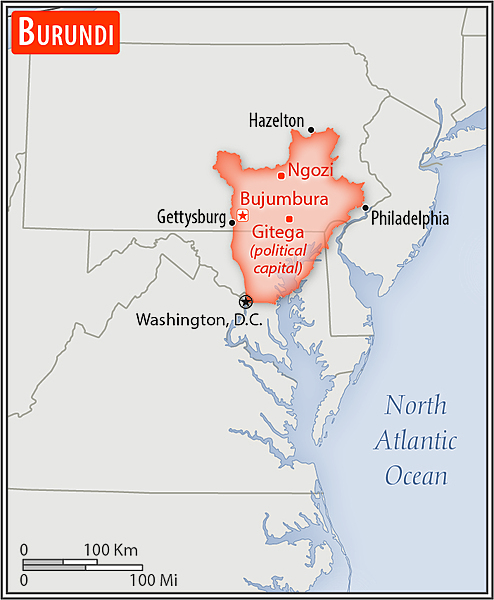

Area - comparative

slightly smaller than Maryland

slightly smaller than Maryland

Background

Established in the 1600s, the Burundi Kingdom has had borders similar to those of modern Burundi since the 1800s. Burundi’s two major ethnic groups, the majority Hutu and minority Tutsi, share a common language and culture and largely lived in peaceful cohabitation under Tutsi monarchs in pre-colonial Burundi. Regional, class, and clan distinctions contributed to social status in the Burundi Kingdom, yielding a complex class structure. German colonial rule in the late 19th and early 20th centuries and Belgian rule after World War I preserved Burundi’s monarchy. Seeking to simplify administration, Belgian colonial officials reduced the number of chiefdoms and eliminated most Hutu chiefs from positions of power. In 1961, the Burundian Tutsi king’s oldest son, Louis RWAGASORE, was murdered by a competing political faction shortly before he was set to become prime minister, triggering increased political competition that contributed to later instability.

Burundi gained its independence from Belgium in 1962 as the Kingdom of Burundi. Revolution in neighboring Rwanda stoked ethnic polarization as the Tutsi increasingly feared violence and loss of political power. A failed Hutu-led coup in 1965 triggered a purge of Hutu officials and set the stage for Tutsi officers to overthrow the monarchy in 1966 and establish a Tutsi-dominated republic. A Hutu rebellion in 1972 resulted in the deaths of several thousand Tutsi civilians and sparked brutal Tutsi-led military reprisals against Hutu civilians which ultimately killed 100,000-200,000 people. International pressure led to a new constitution in 1992 and democratic elections in 1993. Tutsi military officers feared Hutu domination and assassinated Burundi's first democratically elected president, Hutu Melchior NDADAYE, in 1993 after only 100 days in office, sparking a civil war. In 1994, his successor, Cyprien NTARYAMIRA, died when the Rwandan president’s plane he was traveling on was shot down, which triggered the Rwandan genocide and further entrenched ethnic conflict in Burundi. The internationally brokered Arusha Agreement, signed in 2000, and subsequent cease-fire agreements with armed movements ended the 1993-2005 civil war. Burundi’s second democratic elections were held in 2005, resulting in the election of Pierre NKURUNZIZA as president. He was reelected in 2010 and again in 2015 after a controversial court decision allowed him to circumvent a term limit. President Evariste NDAYISHIMIYE -- from NKURUNZIZA’s ruling party -- was elected in 2020.

Burundi gained its independence from Belgium in 1962 as the Kingdom of Burundi. Revolution in neighboring Rwanda stoked ethnic polarization as the Tutsi increasingly feared violence and loss of political power. A failed Hutu-led coup in 1965 triggered a purge of Hutu officials and set the stage for Tutsi officers to overthrow the monarchy in 1966 and establish a Tutsi-dominated republic. A Hutu rebellion in 1972 resulted in the deaths of several thousand Tutsi civilians and sparked brutal Tutsi-led military reprisals against Hutu civilians which ultimately killed 100,000-200,000 people. International pressure led to a new constitution in 1992 and democratic elections in 1993. Tutsi military officers feared Hutu domination and assassinated Burundi's first democratically elected president, Hutu Melchior NDADAYE, in 1993 after only 100 days in office, sparking a civil war. In 1994, his successor, Cyprien NTARYAMIRA, died when the Rwandan president’s plane he was traveling on was shot down, which triggered the Rwandan genocide and further entrenched ethnic conflict in Burundi. The internationally brokered Arusha Agreement, signed in 2000, and subsequent cease-fire agreements with armed movements ended the 1993-2005 civil war. Burundi’s second democratic elections were held in 2005, resulting in the election of Pierre NKURUNZIZA as president. He was reelected in 2010 and again in 2015 after a controversial court decision allowed him to circumvent a term limit. President Evariste NDAYISHIMIYE -- from NKURUNZIZA’s ruling party -- was elected in 2020.

Environmental issues

soil erosion from overgrazing and agricultural expansion; deforestation; wildlife habitat loss

International environmental agreements

party to: Biodiversity, Climate Change, Climate Change-Kyoto Protocol, Climate Change-Paris Agreement, Comprehensive Nuclear Test Ban, Desertification, Endangered Species, Hazardous Wastes, Ozone Layer Protection, Wetlands

signed, but not ratified: Law of the Sea, Nuclear Test Ban

signed, but not ratified: Law of the Sea, Nuclear Test Ban

Military expenditures

3.5% of GDP (2024 est.)

3% of GDP (2023 est.)

2.6% of GDP (2022 est.)

2% of GDP (2021 est.)

2.1% of GDP (2020 est.)

3% of GDP (2023 est.)

2.6% of GDP (2022 est.)

2% of GDP (2021 est.)

2.1% of GDP (2020 est.)

Population below poverty line

51% (2020 est.)

note: % of population with income below national poverty line

note: % of population with income below national poverty line

Household income or consumption by percentage share

lowest 10%: 2.9% (2020 est.)

highest 10%: 29.9% (2020 est.)

note: % share of income accruing to lowest and highest 10% of population

highest 10%: 29.9% (2020 est.)

note: % share of income accruing to lowest and highest 10% of population

Exports - commodities

gold, coffee, tea, tin ores, iron bars (2023)

note: top five export commodities based on value in dollars

note: top five export commodities based on value in dollars

Exports - partners

UAE 59%, Uganda 8%, China 5%, Germany 5%, USA 3% (2023)

note: top five export partners based on percentage share of exports

note: top five export partners based on percentage share of exports

Administrative divisions

5 provinces: Buhumuza, Bujumbura, Burunga, Butanyerera, Gitega

Agricultural products

cassava, bananas, sweet potatoes, beans, maize, vegetables, potatoes, rice, sugarcane, fruits (2023)

note: top ten agricultural products based on tonnage

note: top ten agricultural products based on tonnage

Military and security forces

Burundi National Defense Force (BNDF; Force de Defense Nationale du Burundi, FDNB): Land Force (Army), Naval Force, Air Force, Specialized Units

Ministry of Interior, Community Development, and Public Security: Burundi National Police (Police Nationale du Burundi, PNB) (2024)

note: the Naval Force is responsible for monitoring Burundi’s 175-km shoreline on Lake Tanganyika; the Specialized Units include a special security brigade for the protection of institutions (aka BSPI), commandos, special forces, and military police

Ministry of Interior, Community Development, and Public Security: Burundi National Police (Police Nationale du Burundi, PNB) (2024)

note: the Naval Force is responsible for monitoring Burundi’s 175-km shoreline on Lake Tanganyika; the Specialized Units include a special security brigade for the protection of institutions (aka BSPI), commandos, special forces, and military police

Budget

revenues: $713.694 million (2021 est.)

expenditures: $737.898 million (2021 est.)

note: central government revenues and expenses (excluding grants/extrabudgetary units/social security funds) converted to US dollars at average official exchange rate for year indicated

expenditures: $737.898 million (2021 est.)

note: central government revenues and expenses (excluding grants/extrabudgetary units/social security funds) converted to US dollars at average official exchange rate for year indicated

Capital

name: Gitega (political capital), Bujumbura (commercial capital)

geographic coordinates: 3 25 S, 29 55 E

time difference: UTC+2 (7 hours ahead of Washington, DC, during Standard Time)

etymology: the origin of the name Bujumbura is unclear, but "bu-" is a Bantu prefix meaning "place"

note: in January 2019, the Burundian parliament voted to make Gitega the political capital of the country while Bujumbura would remain its economic capital; as of 2023, the government's move to Gitega remains incomplete

geographic coordinates: 3 25 S, 29 55 E

time difference: UTC+2 (7 hours ahead of Washington, DC, during Standard Time)

etymology: the origin of the name Bujumbura is unclear, but "bu-" is a Bantu prefix meaning "place"

note: in January 2019, the Burundian parliament voted to make Gitega the political capital of the country while Bujumbura would remain its economic capital; as of 2023, the government's move to Gitega remains incomplete

Imports - commodities

fertilizers, cement, packaged medicine, plastic products, cars (2023)

note: top five import commodities based on value in dollars

note: top five import commodities based on value in dollars

Climate

equatorial; high plateau with considerable altitude variation (772 m to 2,670 m above sea level); average annual temperature varies with altitude from 23 to 17 degrees Celsius but is generally moderate; average annual rainfall is about 150 cm with two wet seasons (February to May and September to November) and two dry seasons (June to August and December to January)

Coastline

0 km (landlocked)

Constitution

history: several previous, ratified by referendum 28 February 2005

amendment process: proposed by the president of the republic after consultation with the government or by absolute majority support of the membership in both houses of Parliament; passage requires at least two-thirds majority vote by the Senate membership and at least four-fifths majority vote by the National Assembly; the president can opt to submit amendment bills to a referendum; constitutional articles including those on national unity, the secularity of Burundi, its democratic form of government, and its sovereignty cannot be amended

amendment process: proposed by the president of the republic after consultation with the government or by absolute majority support of the membership in both houses of Parliament; passage requires at least two-thirds majority vote by the Senate membership and at least four-fifths majority vote by the National Assembly; the president can opt to submit amendment bills to a referendum; constitutional articles including those on national unity, the secularity of Burundi, its democratic form of government, and its sovereignty cannot be amended

Exchange rates

Burundi francs (BIF) per US dollar -

Exchange rates:

2,574.052 (2023 est.)

2,034.307 (2022 est.)

1,975.951 (2021 est.)

1,915.046 (2020 est.)

1,845.623 (2019 est.)

Exchange rates:

2,574.052 (2023 est.)

2,034.307 (2022 est.)

1,975.951 (2021 est.)

1,915.046 (2020 est.)

1,845.623 (2019 est.)

Executive branch

chief of state: President Evariste NDAYISHIMIYE (since 18 June 2020)

head of government: Prime Minister Nestor NTAHONTUYE (since 5 August 2025)

cabinet: Council of Ministers appointed by president

election/appointment process: president directly elected by absolute-majority popular vote in 2 rounds, if needed, for a 7-year term (eligible for a second term); vice presidents nominated by the president, endorsed by Parliament

most recent election date: 20 May 2020

election results:

2020: Evariste NDAYISHIMIYE elected president; percent of vote - Evariste NDAYISHIMIYE (CNDD-FDD) 71.5%, Agathon RWASA (CNL) 25.2%, Gaston SINDIMWO (UPRONA) 1.7%, other 1.6%

2015: Pierre NKURUNZIZA reelected president; percent of vote - Pierre NKURUNZIZA (CNDD-FDD) 69.4%, Agathon RWASA (Hope of Burundians - Amizerio y'ABARUNDI) 19%, other 11.6%

expected date of next election: May 2027

head of government: Prime Minister Nestor NTAHONTUYE (since 5 August 2025)

cabinet: Council of Ministers appointed by president

election/appointment process: president directly elected by absolute-majority popular vote in 2 rounds, if needed, for a 7-year term (eligible for a second term); vice presidents nominated by the president, endorsed by Parliament

most recent election date: 20 May 2020

election results:

2020: Evariste NDAYISHIMIYE elected president; percent of vote - Evariste NDAYISHIMIYE (CNDD-FDD) 71.5%, Agathon RWASA (CNL) 25.2%, Gaston SINDIMWO (UPRONA) 1.7%, other 1.6%

2015: Pierre NKURUNZIZA reelected president; percent of vote - Pierre NKURUNZIZA (CNDD-FDD) 69.4%, Agathon RWASA (Hope of Burundians - Amizerio y'ABARUNDI) 19%, other 11.6%

expected date of next election: May 2027

Flag

description: divided by a white diagonal cross into red triangles (top and bottom) and green triangles (on each side) with a white disk at the center bearing three six-pointed red stars outlined in green and arranged in a triangular design

meaning: green stands for hope and optimism, white for purity and peace, and red for the blood shed in the struggle for independence; the three stars represent the major ethnic groups (Hutu, Twa, Tutsi), as well as unity, work, and progress

meaning: green stands for hope and optimism, white for purity and peace, and red for the blood shed in the struggle for independence; the three stars represent the major ethnic groups (Hutu, Twa, Tutsi), as well as unity, work, and progress

Independence

1 July 1962 (from UN trusteeship under Belgian administration)

Industries

light consumer goods (sugar, shoes, soap, beer); cement, assembly of imported components; public works construction; food processing (fruits)

Judicial branch

highest court(s): Supreme Court (consists of 9 judges and organized into judicial, administrative, and cassation chambers); Constitutional Court (consists of 7 members)

judge selection and term of office: Supreme Court judges nominated by the Judicial Service Commission, a 15-member body of judicial and legal profession officials), appointed by the president and confirmed by the Senate; judge tenure NA; Constitutional Court judges appointed by the president and confirmed by the Senate and serve 6-year nonrenewable terms

subordinate courts: Courts of Appeal; County Courts; Courts of Residence; Martial Court; Commercial Court

judge selection and term of office: Supreme Court judges nominated by the Judicial Service Commission, a 15-member body of judicial and legal profession officials), appointed by the president and confirmed by the Senate; judge tenure NA; Constitutional Court judges appointed by the president and confirmed by the Senate and serve 6-year nonrenewable terms

subordinate courts: Courts of Appeal; County Courts; Courts of Residence; Martial Court; Commercial Court

Land boundaries

total: 1,140 km

border countries (3): Democratic Republic of the Congo 236 km; Rwanda 315 km; Tanzania 589 km

border countries (3): Democratic Republic of the Congo 236 km; Rwanda 315 km; Tanzania 589 km

Land use

agricultural land: 83.9% (2023 est.)

arable land: 51.4% (2023 est.)

permanent crops: 13.6% (2023 est.)

permanent pasture: 18.8% (2023 est.)

forest: 10.9% (2023 est.)

other: 5.2% (2023 est.)

arable land: 51.4% (2023 est.)

permanent crops: 13.6% (2023 est.)

permanent pasture: 18.8% (2023 est.)

forest: 10.9% (2023 est.)

other: 5.2% (2023 est.)

Legal system

mixed legal system of Belgian civil law and customary law

Legislative branch

legislature name: Parliament (Parlement)

legislative structure: bicameral

legislative structure: bicameral

Literacy

total population: 71.4% (2020 est.)

male: 78.2% (2020 est.)

female: 66.2% (2020 est.)

male: 78.2% (2020 est.)

female: 66.2% (2020 est.)

Maritime claims

none (landlocked)

International organization participation

ACP, AfDB, ATMIS, AU, CEMAC, CEPGL, CICA, COMESA, EAC, FAO, G-77, IBRD, ICAO, ICGLR, ICRM, IDA, IFAD, IFC, IFRCS, ILO, IMF, Interpol, IOC, IOM, IPU, ISO (correspondent), ITU, ITUC (NGOs), MIGA, NAM, OIF, OPCW, UN, UNCTAD, UNESCO, UNHRC, UNIDO, UNISFA, UNMISS, UNWTO, UPU, WCO, WHO, WIPO, WMO, WTO

National holiday

Independence Day, 1 July (1962)

Nationality

noun: Burundian(s)

adjective: Burundian

adjective: Burundian

Natural resources

nickel, uranium, rare earth oxides, peat, cobalt, copper, platinum, vanadium, arable land, hydropower, niobium, tantalum, gold, tin, tungsten, kaolin, limestone

Geography - note

landlocked; straddles crest of the Nile-Congo watershed; the Kagera, which drains into Lake Victoria, is the most remote headstream of the White Nile

Economic overview

highly agrarian, low-income Sub-Saharan economy; declining foreign assistance; increasing fiscal insolvencies; dense and still growing population; COVID-19 weakened economic recovery and flipped two years of deflation

Political parties

Council for Democracy and the Sustainable Development of Burundi or CODEBU

Front for Democracy in Burundi-Sahwanya or FRODEBU-Sahwanya

National Council for the Defense of Democracy - Front for the Defense of Democracy or CNDD-FDD

National Congress for Liberty or CNL

National Liberation Forces or FNL

Union for National Progress (Union pour le Progress Nationale) or UPRONA

Front for Democracy in Burundi-Sahwanya or FRODEBU-Sahwanya

National Council for the Defense of Democracy - Front for the Defense of Democracy or CNDD-FDD

National Congress for Liberty or CNL

National Liberation Forces or FNL

Union for National Progress (Union pour le Progress Nationale) or UPRONA

Suffrage

18 years of age; universal

Terrain

hilly and mountainous, dropping to a plateau in east, some plains

Government type

presidential republic

Country name

conventional long form: Republic of Burundi

conventional short form: Burundi

local long form: République du Burundi (French)/ Republika y'u Burundi (Kirundi)

local short form: Burundi

former: Urundi, German East Africa, Ruanda-Urundi, Kingdom of Burundi

etymology: name dates from 1966 and is derived from the name of the local Bantu people, the Rundi or Barundi; ba- is the prefix for the people, and bu- is the prefix for the country; the former name, Urundi, is the Swahili version

conventional short form: Burundi

local long form: République du Burundi (French)/ Republika y'u Burundi (Kirundi)

local short form: Burundi

former: Urundi, German East Africa, Ruanda-Urundi, Kingdom of Burundi

etymology: name dates from 1966 and is derived from the name of the local Bantu people, the Rundi or Barundi; ba- is the prefix for the people, and bu- is the prefix for the country; the former name, Urundi, is the Swahili version

Location

Central Africa, east of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, west of Tanzania

Map references

Africa

Irrigated land

230 sq km (2012)

Diplomatic representation in the US

chief of mission: Ambassador Jean Bosco BAREGE (since 27 February 2024)

chancery: 2233 Wisconsin Avenue NW, Washington, DC 20007

telephone: [1] (202) 342-2574

FAX: [1] (202) 342-2578

email address and website: burundiembusadc@gmail.com

Burundi Embassy Washington D.C. (burundiembassy-usa.com)

chancery: 2233 Wisconsin Avenue NW, Washington, DC 20007

telephone: [1] (202) 342-2574

FAX: [1] (202) 342-2578

email address and website: burundiembusadc@gmail.com

Burundi Embassy Washington D.C. (burundiembassy-usa.com)

Internet users

percent of population: 11% (2023 est.)

Internet country code

.bi

Refugees and internally displaced persons

refugees: 91,164 (2024 est.)

IDPs: 92,174 (2024 est.)

stateless persons: 791 (2024 est.)

IDPs: 92,174 (2024 est.)

stateless persons: 791 (2024 est.)

GDP (official exchange rate)

$2.162 billion (2024 est.)

note: data in current dollars at official exchange rate

note: data in current dollars at official exchange rate

Total renewable water resources

12.536 billion cubic meters (2022 est.)

School life expectancy (primary to tertiary education)

total: 10 years (2018 est.)

male: 10 years (2018 est.)

female: 10 years (2018 est.)

male: 10 years (2018 est.)

female: 10 years (2018 est.)

Urbanization

urban population: 14.8% of total population (2023)

rate of urbanization: 5.43% annual rate of change (2020-25 est.)

rate of urbanization: 5.43% annual rate of change (2020-25 est.)

Broadcast media

state-controlled Radio Television Nationale de Burundi (RTNB) operates a TV station and a national radio network; 3 private TV stations and about 10 privately owned radio stations; transmissions of several international broadcasters are available in Bujumbura (2019)

Drinking water source

improved:

urban: 90.7% of population (2022 est.)

rural: 57.7% of population (2022 est.)

total: 62.4% of population (2022 est.)

unimproved:

urban: 9.3% of population (2022 est.)

rural: 42.3% of population (2022 est.)

total: 37.6% of population (2022 est.)

urban: 90.7% of population (2022 est.)

rural: 57.7% of population (2022 est.)

total: 62.4% of population (2022 est.)

unimproved:

urban: 9.3% of population (2022 est.)

rural: 42.3% of population (2022 est.)

total: 37.6% of population (2022 est.)

National anthem(s)

title: "Burundi Bwacu" (Our Beloved Burundi)

lyrics/music: Jean-Baptiste NTAHOKAJA/Marc BARENGAYABO

history: adopted 1962

lyrics/music: Jean-Baptiste NTAHOKAJA/Marc BARENGAYABO

history: adopted 1962

Major urban areas - population

1.207 million BUJUMBURA (capital) (2023)

International law organization participation

has not submitted an ICJ jurisdiction declaration; withdrew from ICCt in October 2017

National symbol(s)

lion

Mother's mean age at first birth

21.5 years (2016/17 est.)

note: data represents median age at first birth among women 25-49

note: data represents median age at first birth among women 25-49

GDP - composition, by end use

household consumption: 75.9% (2023 est.)

government consumption: 30.7% (2023 est.)

investment in fixed capital: 13.1% (2023 est.)

investment in inventories: 0% (2023 est.)

exports of goods and services: 5.3% (2023 est.)

imports of goods and services: -24.4% (2023 est.)

note: figures may not total 100% due to rounding or gaps in data collection

government consumption: 30.7% (2023 est.)

investment in fixed capital: 13.1% (2023 est.)

investment in inventories: 0% (2023 est.)

exports of goods and services: 5.3% (2023 est.)

imports of goods and services: -24.4% (2023 est.)

note: figures may not total 100% due to rounding or gaps in data collection

Dependency ratios

total dependency ratio: 83.9 (2024 est.)

youth dependency ratio: 77.7 (2024 est.)

elderly dependency ratio: 6.2 (2024 est.)

potential support ratio: 16.2 (2024 est.)

youth dependency ratio: 77.7 (2024 est.)

elderly dependency ratio: 6.2 (2024 est.)

potential support ratio: 16.2 (2024 est.)

Citizenship

citizenship by birth: no

citizenship by descent only: the father must be a citizen of Burundi

dual citizenship recognized: no

residency requirement for naturalization: 10 years

citizenship by descent only: the father must be a citizen of Burundi

dual citizenship recognized: no

residency requirement for naturalization: 10 years

Population distribution

one of Africa's most densely populated countries; concentrations tend to be in the north and along the northern shore of Lake Tanganyika in the west; most people live on farms near areas of fertile volcanic soil, as shown in this population distribution map

Electricity access

electrification - total population: 10.3% (2022 est.)

electrification - urban areas: 64%

electrification - rural areas: 1.7%

electrification - urban areas: 64%

electrification - rural areas: 1.7%

Civil aircraft registration country code prefix

9U

Sanitation facility access

improved:

urban: 87.4% of population (2022 est.)

rural: 53.7% of population (2022 est.)

total: 58.6% of population (2022 est.)

unimproved:

urban: 12.6% of population (2022 est.)

rural: 46.3% of population (2022 est.)

total: 41.4% of population (2022 est.)

urban: 87.4% of population (2022 est.)

rural: 53.7% of population (2022 est.)

total: 58.6% of population (2022 est.)

unimproved:

urban: 12.6% of population (2022 est.)

rural: 46.3% of population (2022 est.)

total: 41.4% of population (2022 est.)

Ethnic groups

Hutu, Tutsi, Twa, South Asian

Religions

Christian 93.9% (Roman Catholic 58.6%, Protestant 35.3% [includes Adventist 2.7% and other Protestant religions 32.6%]), Muslim 3.4%, other 1.3%, none 1.3% (2016-17 est.)

Languages

Kirundi (official), French (official), English (official, least spoken), Swahili (2008 est.)

major-language sample(s):

Igitabo Mpuzamakungu c'ibimenyetso bifatika, isoko ntabanduka ku nkuru z'urufatiro. (Kirundi)

The World Factbook, the indispensable source for basic information.

note: data represent languages read and written by people 10 years of age or older; spoken Kirundi is nearly universal

major-language sample(s):

Igitabo Mpuzamakungu c'ibimenyetso bifatika, isoko ntabanduka ku nkuru z'urufatiro. (Kirundi)

The World Factbook, the indispensable source for basic information.

note: data represent languages read and written by people 10 years of age or older; spoken Kirundi is nearly universal

Imports - partners

Tanzania 26%, China 15%, Uganda 10%, Kenya 10%, India 6% (2023)

note: top five import partners based on percentage share of imports

note: top five import partners based on percentage share of imports

Elevation

highest point: unnamed elevation on Mukike Range 2,685 m

lowest point: Lake Tanganyika 772 m

mean elevation: 1,504 m

lowest point: Lake Tanganyika 772 m

mean elevation: 1,504 m

Physician density

0.08 physicians/1,000 population (2022)

Health expenditure

9.1% of GDP (2021)

4.7% of national budget (2022 est.)

4.7% of national budget (2022 est.)

Military and security service personnel strengths

limited available information; estimated 25-30,000 active-duty Defense Force troops (2025)

Military - note

the National Defense Force (FDNB) is responsible for defending Burundi’s territorial integrity and protecting its sovereignty; it has an internal security role, including maintaining and restoring public order if required; the FDNB also participates in providing humanitarian/disaster assistance, countering terrorism, narcotics trafficking, piracy, and illegal arms trade, and protecting the country’s environment; the FDNB conducts limited training with foreign partners such as Russia and participates in regional peacekeeping missions, most recently in the Central African Republic, the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), and Somalia; in recent years the FDNB has conducted operations against anti-government rebel groups based in the neighboring DRC that have carried out sporadic attacks in Burundi, such as the such as National Forces of Liberation (FNL), the Resistance for the Rule of Law-Tabara (aka RED Tabara), and Popular Forces of Burundi (FPB or FOREBU); Burundi has accused Rwanda of supporting the RED-Tabara

the Arusha Accords that ended the 1993-2005 civil war created a unified military by balancing the predominantly Tutsi ex-Burundi Armed Forces (ex-FAB) and the largely Hutu dominated armed movements and requiring the military to have a 50/50 ethnic mix of Tutsis and Hutus (2025)

the Arusha Accords that ended the 1993-2005 civil war created a unified military by balancing the predominantly Tutsi ex-Burundi Armed Forces (ex-FAB) and the largely Hutu dominated armed movements and requiring the military to have a 50/50 ethnic mix of Tutsis and Hutus (2025)

Total water withdrawal

municipal: 43.1 million cubic meters (2022 est.)

industrial: 15 million cubic meters (2022 est.)

agricultural: 222 million cubic meters (2022 est.)

industrial: 15 million cubic meters (2022 est.)

agricultural: 222 million cubic meters (2022 est.)

Waste and recycling

municipal solid waste generated annually: 1.872 million tons (2024 est.)

percent of municipal solid waste recycled: 7.1% (2022 est.)

percent of municipal solid waste recycled: 7.1% (2022 est.)

Major watersheds (area sq km)

Atlantic Ocean drainage: Congo (3,730,881 sq km), (Mediterranean Sea) Nile (3,254,853 sq km)

Major lakes (area sq km)

fresh water lake(s): Lake Tanganyika (shared with Democratic Republic of Congo, Tanzania, and Zambia) - 32,000 sq km

Child marriage

women married by age 15: 2.8% (2017)

women married by age 18: 19% (2017)

men married by age 18: 1.4% (2017)

women married by age 18: 19% (2017)

men married by age 18: 1.4% (2017)

Coal

consumption: 1,000 metric tons (2023 est.)

imports: 10,000 metric tons (2023 est.)

imports: 10,000 metric tons (2023 est.)

Electricity generation sources

fossil fuels: 31.2% of total installed capacity (2023 est.)

solar: 0.5% of total installed capacity (2023 est.)

hydroelectricity: 66.7% of total installed capacity (2023 est.)

biomass and waste: 1.6% of total installed capacity (2023 est.)

solar: 0.5% of total installed capacity (2023 est.)

hydroelectricity: 66.7% of total installed capacity (2023 est.)

biomass and waste: 1.6% of total installed capacity (2023 est.)

Petroleum

refined petroleum consumption: 6,000 bbl/day (2023 est.)

Currently married women (ages 15-49)

58.2% (2017 est.)

Remittances

7.5% of GDP (2023 est.)

4.9% of GDP (2022 est.)

6.1% of GDP (2021 est.)

note: personal transfers and compensation between resident and non-resident individuals/households/entities

4.9% of GDP (2022 est.)

6.1% of GDP (2021 est.)

note: personal transfers and compensation between resident and non-resident individuals/households/entities

Legislative branch - lower chamber

chamber name: National Assembly (Inama Nshingamateka)

number of seats: 111 (all directly elected)

electoral system: proportional representation

scope of elections: full renewal

term in office: 5 years

most recent election date: 6/5/2025

parties elected and seats per party: National Council for the Defense of Democracy - Front for the Defense of Democracy (CNDD-FDD) (108); Other (3)

percentage of women in chamber: 39.6%

expected date of next election: June 2030

note: 60% of seats in the National Assembly are allocated to Hutus and 40% to Tutsis; 3 seats are reserved for Twas; 30% of total seats are reserved for women

number of seats: 111 (all directly elected)

electoral system: proportional representation

scope of elections: full renewal

term in office: 5 years

most recent election date: 6/5/2025

parties elected and seats per party: National Council for the Defense of Democracy - Front for the Defense of Democracy (CNDD-FDD) (108); Other (3)

percentage of women in chamber: 39.6%

expected date of next election: June 2030

note: 60% of seats in the National Assembly are allocated to Hutus and 40% to Tutsis; 3 seats are reserved for Twas; 30% of total seats are reserved for women

Legislative branch - upper chamber

chamber name: Senate (Inama Nkenguzamateka)

number of seats: 13 (all indirectly elected)

scope of elections: full renewal

term in office: 5 years

most recent election date: 7/23/2025

parties elected and seats per party: National Council for the Defense of Democracy - Front for the Defense of Democracy (CNDD-FDD) (10)

percentage of women in chamber: 46.2%

expected date of next election: July 2030

note: 3 seats in the Senate are reserved for Twas, and 30% of all votes are reserved for women

number of seats: 13 (all indirectly elected)

scope of elections: full renewal

term in office: 5 years

most recent election date: 7/23/2025

parties elected and seats per party: National Council for the Defense of Democracy - Front for the Defense of Democracy (CNDD-FDD) (10)

percentage of women in chamber: 46.2%

expected date of next election: July 2030

note: 3 seats in the Senate are reserved for Twas, and 30% of all votes are reserved for women

National color(s)

red, white, green

Particulate matter emissions

26.3 micrograms per cubic meter (2019 est.)

Labor force

6.107 million (2024 est.)

note: number of people ages 15 or older who are employed or seeking work

note: number of people ages 15 or older who are employed or seeking work

Youth unemployment rate (ages 15-24)

total: 1.6% (2024 est.)

male: 2.1% (2024 est.)

female: 1.2% (2024 est.)

note: % of labor force ages 15-24 seeking employment

male: 2.1% (2024 est.)

female: 1.2% (2024 est.)

note: % of labor force ages 15-24 seeking employment

Debt - external

$805.174 million (2023 est.)

note: present value of external debt in current US dollars

note: present value of external debt in current US dollars

Maternal mortality ratio

392 deaths/100,000 live births (2023 est.)

Reserves of foreign exchange and gold

$90.35 million (2023 est.)

$158.53 million (2022 est.)

$266.164 million (2021 est.)

note: holdings of gold (year-end prices)/foreign exchange/special drawing rights in current dollars

$158.53 million (2022 est.)

$266.164 million (2021 est.)

note: holdings of gold (year-end prices)/foreign exchange/special drawing rights in current dollars

Unemployment rate

1% (2024 est.)

1% (2023 est.)

1% (2022 est.)

note: % of labor force seeking employment

1% (2023 est.)

1% (2022 est.)

note: % of labor force seeking employment

Population

total: 13,590,102 (2024 est.)

male: 6,755,456

female: 6,834,646

male: 6,755,456

female: 6,834,646

Carbon dioxide emissions

838,000 metric tonnes of CO2 (2023 est.)

from coal and metallurgical coke: 32,000 metric tonnes of CO2 (2023 est.)

from petroleum and other liquids: 806,000 metric tonnes of CO2 (2023 est.)

from coal and metallurgical coke: 32,000 metric tonnes of CO2 (2023 est.)

from petroleum and other liquids: 806,000 metric tonnes of CO2 (2023 est.)

Area

total : 27,830 sq km

land: 25,680 sq km

water: 2,150 sq km

land: 25,680 sq km

water: 2,150 sq km

Taxes and other revenues

15.6% (of GDP) (2021 est.)

note: central government tax revenue as a % of GDP

note: central government tax revenue as a % of GDP

Real GDP (purchasing power parity)

$11.739 billion (2024 est.)

$11.343 billion (2023 est.)

$11.048 billion (2022 est.)

note: data in 2021 dollars

$11.343 billion (2023 est.)

$11.048 billion (2022 est.)

note: data in 2021 dollars

Airports

6 (2025)

Gini Index coefficient - distribution of family income

37.5 (2020 est.)

note: index (0-100) of income distribution; higher values represent greater inequality

note: index (0-100) of income distribution; higher values represent greater inequality

Inflation rate (consumer prices)

20.2% (2024 est.)

26.9% (2023 est.)

18.8% (2022 est.)

note: annual % change based on consumer prices

26.9% (2023 est.)

18.8% (2022 est.)

note: annual % change based on consumer prices

Current account balance

-$625.597 million (2023 est.)

-$621.969 million (2022 est.)

-$393.88 million (2021 est.)

note: balance of payments - net trade and primary/secondary income in current dollars

-$621.969 million (2022 est.)

-$393.88 million (2021 est.)

note: balance of payments - net trade and primary/secondary income in current dollars

Real GDP per capita

$800 (2024 est.)

$800 (2023 est.)

$800 (2022 est.)

note: data in 2021 dollars

$800 (2023 est.)

$800 (2022 est.)

note: data in 2021 dollars

Broadband - fixed subscriptions

total: 3,000 (2023 est.)

subscriptions per 100 inhabitants: (2023 est.) less than 1

subscriptions per 100 inhabitants: (2023 est.) less than 1

Tobacco use

total: 9.1% (2025 est.)

male: 14% (2025 est.)

female: 4.3% (2025 est.)

male: 14% (2025 est.)

female: 4.3% (2025 est.)

Obesity - adult prevalence rate

5.4% (2016)

Energy consumption per capita

946,000 Btu/person (2023 est.)

Electricity

installed generating capacity: 131,000 kW (2023 est.)

consumption: 444.018 million kWh (2023 est.)

imports: 100 million kWh (2023 est.)

transmission/distribution losses: 39.994 million kWh (2023 est.)

consumption: 444.018 million kWh (2023 est.)

imports: 100 million kWh (2023 est.)

transmission/distribution losses: 39.994 million kWh (2023 est.)

Children under the age of 5 years underweight

28.3% (2024 est.)

Imports

$1.433 billion (2023 est.)

$1.42 billion (2022 est.)

$1.166 billion (2021 est.)

note: balance of payments - imports of goods and services in current dollars

$1.42 billion (2022 est.)

$1.166 billion (2021 est.)

note: balance of payments - imports of goods and services in current dollars

Exports

$378.229 million (2023 est.)

$333.637 million (2022 est.)

$302.752 million (2021 est.)

note: balance of payments - exports of goods and services in current dollars

$333.637 million (2022 est.)

$302.752 million (2021 est.)

note: balance of payments - exports of goods and services in current dollars

Telephones - fixed lines

total subscriptions: 14,000 (2023 est.)

subscriptions per 100 inhabitants: (2023 est.) less than 1

subscriptions per 100 inhabitants: (2023 est.) less than 1

Alcohol consumption per capita

total: 4.07 liters of pure alcohol (2019 est.)

beer: 1.84 liters of pure alcohol (2019 est.)

wine: 0 liters of pure alcohol (2019 est.)

spirits: 0 liters of pure alcohol (2019 est.)

other alcohols: 2.23 liters of pure alcohol (2019 est.)

beer: 1.84 liters of pure alcohol (2019 est.)

wine: 0 liters of pure alcohol (2019 est.)

spirits: 0 liters of pure alcohol (2019 est.)

other alcohols: 2.23 liters of pure alcohol (2019 est.)

Life expectancy at birth

total population: 68.1 years (2024 est.)

male: 66 years

female: 70.3 years

male: 66 years

female: 70.3 years

Real GDP growth rate

3.5% (2024 est.)

2.7% (2023 est.)

1.8% (2022 est.)

note: annual GDP % growth based on constant local currency

2.7% (2023 est.)

1.8% (2022 est.)

note: annual GDP % growth based on constant local currency

Industrial production growth rate

-0.2% (2024 est.)

note: annual % change in industrial value added based on constant local currency

note: annual % change in industrial value added based on constant local currency

GDP - composition, by sector of origin

agriculture: 25.3% (2023 est.)

industry: 9.6% (2023 est.)

services: 49% (2023 est.)

note: figures may not total 100% due to non-allocated consumption not captured in sector-reported data

industry: 9.6% (2023 est.)

services: 49% (2023 est.)

note: figures may not total 100% due to non-allocated consumption not captured in sector-reported data

Education expenditure

4.9% of GDP (2021 est.)

14.4% national budget (2025 est.)

14.4% national budget (2025 est.)

Military equipment inventories and acquisitions

the military has a mix of mostly older armaments typically of French, Russian, and Soviet origin, and a smaller selection of more modern equipment from such countries as China, Egypt, South Africa, and the US (2025)

Military service age and obligation

18 years of age for voluntary military service for men and women (2025)

Military deployments

770 Central African Republic (MINUSCA); up to 10,000 Democratic Republic of the Congo (2025)

Gross reproduction rate

2.43 (2025 est.)

Net migration rate

-0.81 migrant(s)/1,000 population (2025 est.)

Median age

total: 17.6 years (2025 est.)

male: 18 years

female: 18.7 years

male: 18 years

female: 18.7 years

Total fertility rate

4.94 children born/woman (2025 est.)

Infant mortality rate

total: 35.3 deaths/1,000 live births (2025 est.)

male: 39.7 deaths/1,000 live births

female: 31.5 deaths/1,000 live births

male: 39.7 deaths/1,000 live births

female: 31.5 deaths/1,000 live births

Telephones - mobile cellular

total subscriptions: 8.65 million (2023 est.)

subscriptions per 100 inhabitants: 58 (2022 est.)

subscriptions per 100 inhabitants: 58 (2022 est.)

Death rate

5.51 deaths/1,000 population (2025 est.)

Birth rate

35.91 births/1,000 population (2025 est.)

Population growth rate

2.96% (2025 est.)