Togo - TG - TGO - TOG - Africa

Togo Images

Togo Factbook Data

Diplomatic representation from the US

embassy: Boulevard Eyadema

B.P. 852, Lomé

mailing address: 2300 Lome Place, Washington, DC 20521-2300

telephone: [228] 2261-5470

FAX: [228] 2261-5501

email address and website:

consularLome@state.gov

https://tg.usembassy.gov/

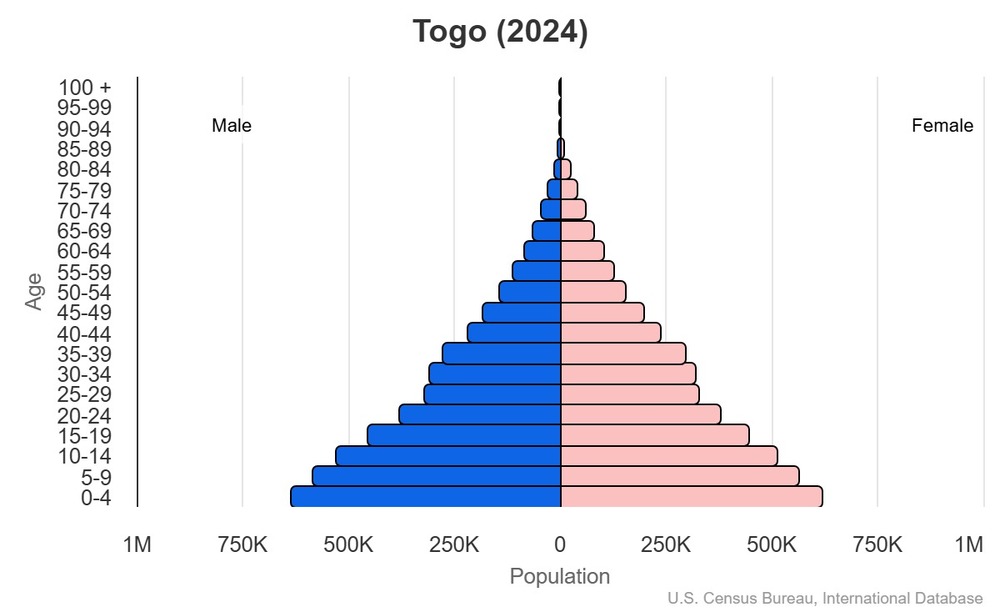

Age structure

15-64 years: 57% (male 2,486,142/female 2,597,914)

65 years and over: 4.3% (2024 est.) (male 159,596/female 225,725)

For additional information, please see the entry for Population pyramid on the Definitions and Notes page.

Geographic coordinates

Sex ratio

0-14 years: 1.03 male(s)/female

15-64 years: 0.96 male(s)/female

65 years and over: 0.71 male(s)/female

total population: 0.97 male(s)/female (2024 est.)

Natural hazards

Area - comparative

Background

From the 11th to the 16th centuries, various ethnic groups settled the Togo region. From the 16th to the 18th centuries, the coastal region became a major trading center for enslaved people, and the surrounding region took on the name of "The Slave Coast." In 1884, Germany declared the area a protectorate called Togoland, which included present-day Togo. After World War I, colonial rule over Togo was transferred to France. French Togoland became Togo upon independence in 1960.

Gen. Gnassingbe EYADEMA, installed as military ruler in 1967, ruled Togo with a heavy hand for almost four decades. Despite the facade of multi-party elections instituted in the early 1990s, EYADEMA largely dominated the government. His Rally of the Togolese People (RPT) party has been in power almost continually since 1967, with its successor, the Union for the Republic, maintaining a majority of seats in today's legislature. Upon EYADEMA's death in 2005, the military installed his son, Faure GNASSINGBE, as president and then engineered his formal election two months later. Togo held its first relatively free and fair legislative elections in 2007. Since then, GNASSINGBE has started the country along a gradual path to democratic reform. Togo has held multiple presidential and legislative elections, and in 2019, the country held its first local elections in 32 years.

Despite those positive moves, political reconciliation has moved slowly, and the country experiences periodic outbursts of protests from frustrated citizens, leading to violence between security forces and protesters. Constitutional changes in 2019 to institute a runoff system in presidential elections and to establish term limits have done little to reduce the resentment many Togolese feel after more than 50 years of one-family rule. GNASSINGBE became eligible for his current fourth term and one additional fifth term under the new rules. The next presidential election is set for 2025.

Environmental issues

International environmental agreements

signed, but not ratified: none of the selected agreements

Military expenditures

3% of GDP (2023 est.)

4% of GDP (2022 est.)

2.8% of GDP (2021 est.)

2.8% of GDP (2020 est.)

Population below poverty line

note: % of population with income below national poverty line

Household income or consumption by percentage share

highest 10%: 29.6% (2021 est.)

note: % share of income accruing to lowest and highest 10% of population

Exports - commodities

note: top five export commodities based on value in dollars

Exports - partners

note: top five export partners based on percentage share of exports

Administrative divisions

Agricultural products

note: top ten agricultural products based on tonnage

Military and security forces

Ministry of Security and Civil Protection: Togolese Police (2025)

note: the Police and GNT are responsible for law enforcement and maintenance of order within the country; the GNT is also responsible for migration and border enforcement; the GNT falls under the Ministry of the Armed Forces but also reports to the Ministry of Security and Civil Protection on many matters involving law enforcement and internal security; in 2022, the Ministry of the Armed Forces was made part of the Office of the Presidency

Budget

expenditures: $2.407 billion (2023 est.)

note: central government revenues and expenses (excluding grants/extrabudgetary units/social security funds) converted to US dollars at average official exchange rate for year indicated

Capital

geographic coordinates: 6 07 N, 1 13 E

time difference: UTC 0 (5 hours ahead of Washington, DC, during Standard Time)

etymology: the name comes from a local word meaning "little market"

Imports - commodities

note: top five import commodities based on value in dollars

Climate

Coastline

Constitution

amendment process: proposed by the president of the republic or supported by at least one fifth of the National Assembly membership; passage requires four-fifths majority vote by the Assembly; a referendum is required if approved by only two-thirds majority of the Assembly or if requested by the president; constitutional articles on the republican and secular form of government cannot be amended

Exchange rates

Exchange rates:

606.345 (2024 est.)

606.57 (2023 est.)

623.76 (2022 est.)

554.531 (2021 est.)

575.586 (2020 est.)

Executive branch

head of government: President of Council of Ministers Faure GNASSINGBE (since 3 May 2025)

cabinet: Council of Ministers appointed by the president on the advice of the president of the council of ministers

election/appointment process: president is appointed by the national assembly for one six-year term; the president of the council of ministers is the leader of the majority party in the national assembly and is confirmed by the Constitutional Court with no term limits

election results:

2020: Faure GNASSINGBE reelected president; percent of vote - Faure GNASSINGBE (UNIR) 70.8%, Agbeyome KODJO (MPDD) 19.5%, Jean-Pierre FABRE (ANC) 4.7%, other 5%

2015: Faure GNASSINGBE reelected president; percent of vote - Faure GNASSINGBE (UNIR) 58.8%, Jean-Pierre FABRE (ANC) 35.2%, Tchaboure GOGUE (ADDI) 4%, other 2%

note: in May 2024, the President signed into law changes to the constitution that converted the presidential system to a parliamentary republic and created the President of Council of Ministers position

Flag

meaning: the five horizontal stripes stand for the country's regions; red stands for the people's loyalty and patriotism; green for hope, fertility, and agriculture; yellow for mineral wealth and faith that hard work and strength will bring prosperity; the star symbolizes life, purity, peace, dignity, and national independence

history: uses the colors of the Pan-African movement

Independence

Industries

Judicial branch

judge selection and term of office: Supreme Court president appointed by decree of the president of the republic on the proposal of the Supreme Council of the Magistracy, a 9-member judicial, advisory, and disciplinary body; other judicial appointments and judge tenure NA; Constitutional Court judges appointed by the National Assembly; judge tenure NA

subordinate courts: Court of Assizes (sessions court); Appeal Court; tribunals of first instance (divided into civil, commercial, and correctional chambers; Court of State Security; military tribunal

Land boundaries

border countries (3): Benin 651 km; Burkina Faso 131 km; Ghana 1,098 km

Land use

arable land: 48.7% (2023 est.)

permanent crops: 3.1% (2023 est.)

permanent pasture: 18.4% (2023 est.)

forest: 22.4% (2023 est.)

other: 7.4% (2023 est.)

Legal system

Legislative branch

legislative structure: bicameral

note: party lists are required to contain equal numbers of men and women

Literacy

male: 82.8% (2022 est.)

female: 63.7% (2022 est.)

Maritime claims

exclusive economic zone: 200 nm

note: the US does not recognize the territorial sea claim

International organization participation

National holiday

Nationality

adjective: Togolese

Natural resources

Geography - note

Economic overview

Political parties

Alliance of Democrats for Integral Development or ADDI

Democratic Convention of African Peoples or CDPA

Democratic Forces for the Republic or FDR

National Alliance for Change or ANC

New Togolese Commitment

Pan-African National Party or PNP

Pan-African Patriotic Convergence or CPP

Patriotic Movement for Democracy and Development or MPDD

Socialist Pact for Renewal or PSR

The Togolese Party

Union of Forces for Change or UFC

Union for the Republic or UNIR

Railways

narrow gauge: 568 km (2014) 1.000-m gauge

Suffrage

Terrain

Government type

Country name

conventional short form: Togo

local long form: République Togolaise

local short form: none

former: French Togoland

etymology: the name derives from the town of Togodo (now Togoville) on the northern shore of Lake Togo; the town's name probably comes from the lake's name, which is composed of the Ewe words to ("water") and go ("shore")

Location

Map references

Irrigated land

Diplomatic representation in the US

chancery: 2208 Massachusetts Avenue NW, Washington, DC 20008

telephone: [1] (202) 234-4212

FAX: [1] (202) 232-3190

email address and website:

embassyoftogo@hotmail.com

https://embassyoftogousa.com/

Internet users

Internet country code

Refugees and internally displaced persons

IDPs: 18,429 (2024 est.)

GDP (official exchange rate)

note: data in current dollars at official exchange rate

Total renewable water resources

School life expectancy (primary to tertiary education)

male: 13 years (2017 est.)

female: 11 years (2017 est.)

Urbanization

rate of urbanization: 3.6% annual rate of change (2020-25 est.)

Broadcast media

Drinking water source

urban: 87% of population (2022 est.)

rural: 58.5% of population (2022 est.)

total: 71% of population (2022 est.)

unimproved:

urban: 13% of population (2022 est.)

rural: 41.5% of population (2022 est.)

total: 29% of population (2022 est.)

National anthem(s)

lyrics/music: Alex CASIMIR-DOSSEH

history: adopted 1960, restored 1992; anthem was replaced during one-party rule between 1979 and 1992

Major urban areas - population

International law organization participation

Physician density

Hospital bed density

National symbol(s)

Mother's mean age at first birth

note: data represents median age at first birth among women 25-29

GDP - composition, by end use

government consumption: 13.1% (2024 est.)

investment in fixed capital: 22.3% (2024 est.)

investment in inventories: 0% (2024 est.)

exports of goods and services: 24.4% (2024 est.)

imports of goods and services: -38.1% (2024 est.)

note: figures may not total 100% due to rounding or gaps in data collection

Citizenship

citizenship by descent only: at least one parent must be a citizen of Togo

dual citizenship recognized: yes

residency requirement for naturalization: 5 years

Population distribution

Electricity access

electrification - urban areas: 96.5%

electrification - rural areas: 25%

Civil aircraft registration country code prefix

Sanitation facility access

urban: 82% of population (2022 est.)

rural: 19.2% of population (2022 est.)

total: 46.7% of population (2022 est.)

unimproved:

urban: 18% of population (2022 est.)

rural: 80.8% of population (2022 est.)

total: 53.3% of population (2022 est.)

Ethnic groups

note: Togo has an estimated 37 ethnic groups

Religions

Languages

Imports - partners

note: top five import partners based on percentage share of imports

Elevation

lowest point: Atlantic Ocean 0 m

mean elevation: 236 m

Health expenditure

2.6% of national budget (2022 est.)

Military - note

since its creation in 1963, the Togolese military has had a history of involvement in the country’s politics, including assassinations, coups, and a crackdown in 2005 that killed hundreds of civilians; over the past decade, it has made efforts to reform and professionalize, which have included increasing its role in UN peacekeeping activities, participating in multinational exercises, and receiving training from foreign partners, particularly France and the US; in addition, Togo has established a regional peacekeeping training center for military and police in Lome (2025)

Military and security service personnel strengths

Military equipment inventories and acquisitions

Total water withdrawal

industrial: 6.3 million cubic meters (2022 est.)

agricultural: 76 million cubic meters (2022 est.)

Waste and recycling

percent of municipal solid waste recycled: 3.5% (2022 est.)

Major watersheds (area sq km)

Terrorist group(s)

note: details about the history, aims, leadership, organization, areas of operation, tactics, targets, weapons, size, and sources of support of the group(s) appear(s) in the Terrorism reference guide

National heritage

selected World Heritage Site locales: Koutammakou; the Land of the Batammariba

Child marriage

women married by age 18: 24.8% (2017)

men married by age 18: 2.6% (2017)

Coal

exports: 10 metric tons (2023 est.)

imports: 163,000 metric tons (2023 est.)

Electricity generation sources

solar: 11.9% of total installed capacity (2023 est.)

hydroelectricity: 8.7% of total installed capacity (2023 est.)

biomass and waste: 0.1% of total installed capacity (2023 est.)

Natural gas

imports: 176.16 million cubic meters (2023 est.)

Petroleum

Gross reproduction rate

Currently married women (ages 15-49)

Remittances

8% of GDP (2022 est.)

7.8% of GDP (2021 est.)

note: personal transfers and compensation between resident and non-resident individuals/households/entities

Ports

large: 0

medium: 1

small: 0

very small: 1

ports with oil terminals: 2

key ports: Kpeme, Lome

Legislative branch - lower chamber

number of seats: 113 (all directly elected)

electoral system: proportional representation

scope of elections: full renewal

term in office: 6 years

most recent election date: 4/29/2024

parties elected and seats per party: Union for the Republic (UNIR) (108); Other (5)

percentage of women in chamber: 15%

expected date of next election: April 2030

Legislative branch - upper chamber

number of seats: 61 (41 directly elected; 20 appointed)

scope of elections: full renewal

term in office: 6 years

most recent election date: 2/15/2025

parties elected and seats per party: Union for the Republic (UNIR) (34); Independents (3); Other (4)

percentage of women in chamber: 24.6%

expected date of next election: February 2031

National color(s)

Particulate matter emissions

Methane emissions

agriculture: 51.8 kt (2019-2021 est.)

waste: 31.3 kt (2019-2021 est.)

other: 10.4 kt (2019-2021 est.)

Labor force

note: number of people ages 15 or older who are employed or seeking work

Youth unemployment rate (ages 15-24)

male: 3.3% (2024 est.)

female: 3.5% (2024 est.)

note: % of labor force ages 15-24 seeking employment

Net migration rate

Median age

male: 19.9 years

female: 21.4 years

Debt - external

note: present value of external debt in current US dollars

Maternal mortality ratio

Total fertility rate

Unemployment rate

2% (2023 est.)

2% (2022 est.)

note: % of labor force seeking employment

Carbon dioxide emissions

from coal and metallurgical coke: 372,000 metric tonnes of CO2 (2023 est.)

from petroleum and other liquids: 1.941 million metric tonnes of CO2 (2023 est.)

from consumed natural gas: 343,000 metric tonnes of CO2 (2023 est.)

Area

land: 54,385 sq km

water: 2,400 sq km

Taxes and other revenues

note: central government tax revenue as a % of GDP

Real GDP (purchasing power parity)

$25.75 billion (2023 est.)

$24.199 billion (2022 est.)

note: data in 2021 dollars

Airports

Infant mortality rate

male: 43 deaths/1,000 live births

female: 33.7 deaths/1,000 live births

Gini Index coefficient - distribution of family income

note: index (0-100) of income distribution; higher values represent greater inequality

Inflation rate (consumer prices)

5.3% (2023 est.)

7.6% (2022 est.)

note: annual % change based on consumer prices

Current account balance

-$55.444 million (2019 est.)

-$184.852 million (2018 est.)

note: balance of payments - net trade and primary/secondary income in current dollars

Real GDP per capita

$2,800 (2023 est.)

$2,700 (2022 est.)

note: data in 2021 dollars

Broadband - fixed subscriptions

subscriptions per 100 inhabitants: 1 (2023 est.)

Tobacco use

male: 9.3% (2025 est.)

female: 0.7% (2025 est.)

Obesity - adult prevalence rate

Energy consumption per capita

Death rate

Birth rate

Electricity

consumption: 1.815 billion kWh (2023 est.)

imports: 1.1 billion kWh (2023 est.)

transmission/distribution losses: 206.938 million kWh (2023 est.)

Merchant marine

by type: bulk carrier 1, container ship 10, general cargo 250, oil tanker 56, other 80

Children under the age of 5 years underweight

Imports

$2.261 billion (2019 est.)

$2.329 billion (2018 est.)

note: balance of payments - imports of goods and services in current dollars

Exports

$1.665 billion (2019 est.)

$1.703 billion (2018 est.)

note: balance of payments - exports of goods and services in current dollars

Alcohol consumption per capita

beer: 0.78 liters of pure alcohol (2019 est.)

wine: 0.09 liters of pure alcohol (2019 est.)

spirits: 0.2 liters of pure alcohol (2019 est.)

other alcohols: 0.33 liters of pure alcohol (2019 est.)

Life expectancy at birth

male: 69.5 years

female: 74.7 years

Real GDP growth rate

6.4% (2023 est.)

5.8% (2022 est.)

note: annual GDP % growth based on constant local currency

Industrial production growth rate

note: annual % change in industrial value added based on constant local currency

GDP - composition, by sector of origin

industry: 20% (2024 est.)

services: 52% (2024 est.)

note: figures may not total 100% due to non-allocated consumption not captured in sector-reported data

Education expenditure

11.6% national budget (2024 est.)

Population growth rate

Military service age and obligation

Dependency ratios

youth dependency ratio: 66.7 (2025 est.)

elderly dependency ratio: 8 (2025 est.)

potential support ratio: 12.6 (2025 est.)

Population

male: 4,488,825

female: 4,654,614

Telephones - mobile cellular

subscriptions per 100 inhabitants: 81 (2024 est.)

Telephones - fixed lines

subscriptions per 100 inhabitants: 1 (2023 est.) less than 1