Sudan - SD - SDN - SUD - Africa

Sudan Images

Sudan Factbook Data

Diplomatic representation from the US

embassy: P.O. Box 699, Kilo 10, Soba, Khartoum

mailing address: 2200 Khartoum Place, Washington DC 20521-2200

telephone: [249] 187-0-22000

email address and website:

ACSKhartoum@state.gov

https://sd.usembassy.gov/

note: the U.S. Embassy in Khartoum suspended operations (to include visa, passport, and other routine consular services) on 22 April 2023

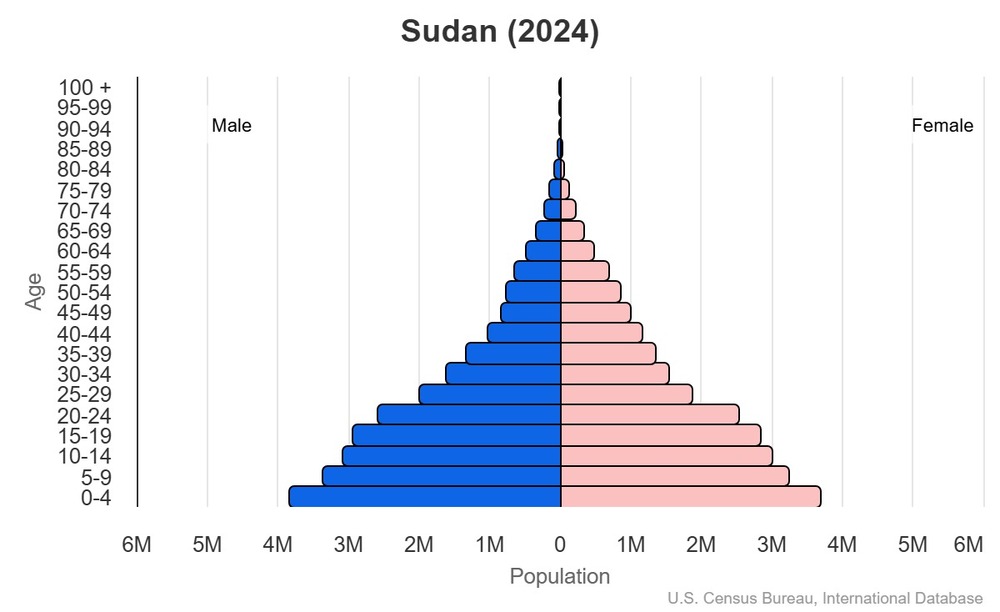

Age structure

15-64 years: 56.7% (male 14,211,514/female 14,390,486)

65 years and over: 3.2% (2024 est.) (male 845,125/female 792,357)

For additional information, please see the entry for Population pyramid on the Definitions and Notes page.

Geographic coordinates

Sex ratio

0-14 years: 1.03 male(s)/female

15-64 years: 0.99 male(s)/female

65 years and over: 1.07 male(s)/female

total population: 1.01 male(s)/female (2024 est.)

Natural hazards

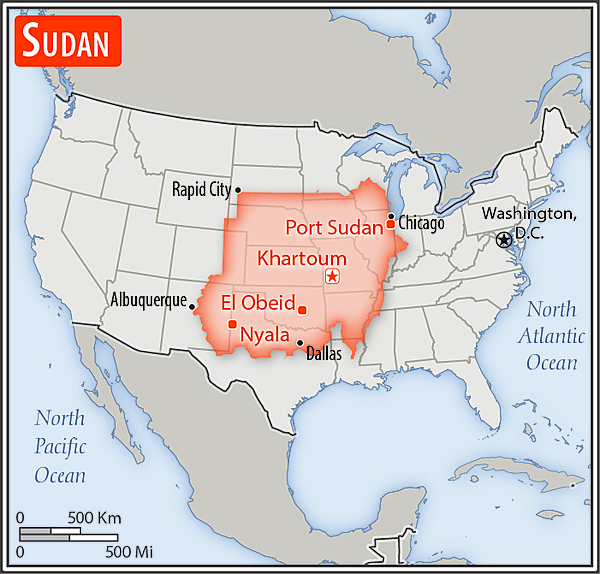

Area - comparative

slightly less than one-fifth the size of the US

Background

Long referred to as Nubia, modern-day Sudan was the site of the Kingdom of Kerma (ca. 2500-1500 B.C.) until it was absorbed into the New Kingdom of Egypt. By the 11th century B.C., the Kingdom of Kush gained independence from Egypt; it lasted in various forms until the middle of the 4th century A.D. After the fall of Kush, the Nubians formed three Christian kingdoms of Nobatia, Makuria, and Alodia, with the latter two enduring until around 1500. Between the 14th and 15th centuries, Arab nomads settled much of Sudan, leading to extensive Islamization between the 16th and 19th centuries. Following Egyptian occupation early in the 19th century, an agreement in 1899 set up a joint British-Egyptian government in Sudan, but it was effectively a British colony.

Military regimes favoring Islamic-oriented governments have dominated national politics since Sudan gained independence from Anglo-Egyptian co-rule in 1956. During most of the second half of the 20th century, Sudan was embroiled in two prolonged civil wars rooted in northern domination of the largely non-Muslim, non-Arab southern portion of the country. The first civil war ended in 1972, but another broke out in 1983. Peace talks gained momentum in 2002-04, and the final North/South Comprehensive Peace Agreement in 2005 granted the southern rebels autonomy for six years, followed by a referendum on independence for Southern Sudan. South Sudan became independent in 2011, but Sudan and South Sudan have yet to fully implement security and economic agreements to normalize relations between the two countries. Sudan has also faced conflict in Darfur, Southern Kordofan, and Blue Nile starting in 2003.

In 2019, after months of nationwide protests, the 30-year reign of President Omar Hassan Ahmad al-BASHIR ended when the military forced him out. Economist and former international civil servant Abdalla HAMDOUK al-Kinani was selected to serve as the prime minister of a transitional government as the country prepared for elections in 2022. In late 2021, however, the Sudanese military ousted HAMDOUK and his government and replaced civilian members of the Sovereign Council (Sudan’s collective Head of State) with individuals selected by the military. HAMDOUK was briefly reinstated but resigned in January 2022. General Abd-al-Fatah al-BURHAN Abd-al-Rahman, the Chair of Sudan’s Sovereign Council and Commander-in-Chief of the Sudanese Armed Forces, currently serves as de facto head of state and government. He presides over a Sovereign Council consisting of military leaders, former armed opposition group representatives, and military-appointed civilians. A cabinet of acting ministers handles day-to-day administration.

Environmental issues

International environmental agreements

signed, but not ratified: none of the selected agreements

Military expenditures

1% of GDP (2020 est.)

2.4% of GDP (2019 est.)

2% of GDP (2018 est.)

3.6% of GDP (2017 est.)

note: many defense expenditures are probably off-budget

Exports - commodities

note: top five export commodities based on value in dollars

Exports - partners

note: top five export partners based on percentage share of exports

Administrative divisions

note: the peace agreement signed in 2020 included a provision to establish a system of governance to restructure the country's current 18 states into regions

Agricultural products

note: top ten agricultural products based on tonnage

Military and security forces

Ministry of Interior: Sudan Police Forces (SPF), Central Reserve Police (CRP) (2025)

note 1: the RSF is a semi-autonomous paramilitary force formed in 2013 to fight armed rebel groups in Sudan, with Mohammed Hamdan DAGALO (aka Hemeti) as its commander; it was initially placed under the National Intelligence and Security Service, then came under the direct command of former president Omar al-BASHIR, who boosted the RSF as his own personal security force; as a result, the RSF was better funded and equipped than the regular armed forces; the RSF has since recruited from all parts of Sudan beyond its original Darfuri Arab groups but remains under the personal patronage and control of DAGALO

note 2: the Central Reserve Police (aka Abu Tira) is a combat-trained paramilitary force

note 3: the October 2020 peace agreement provided for the establishment of a Joint Security Keeping Forces (JSKF) tasked with securing the Darfur region in the place of the UN African Union Hybrid Operation in Darfur (UNAMID), a joint African Union-UN peacekeeping force that operated in the war-torn region from 2007-December 2020; the force was intended to include the SAF, RSF, police, intelligence, and representatives from armed groups involved in peace negotiations; while the first 2,000 members of the JSKF completed training in September 2022, the status of the force since the start of the civil war is not available

note 4: there are also numerous armed militias operating in Sudan

Budget

expenditures: $9.103 billion (2015 est.)

note: central government revenues and expenses (excluding grants/extrabudgetary units/social security funds) converted to US dollars at average official exchange rate for year indicated

Capital

geographic coordinates: 15 36 N, 32 32 E

time difference: UTC+3 (8 hours ahead of Washington, DC, during Standard Time)

etymology: the name derives from the Arabic words ras (head or end) and al-khurtum (elephant's trunk), referring to the narrow strip of land between the Blue and White Niles where the city is located

Imports - commodities

note: top five import commodities based on value in dollars

Climate

Coastline

Constitution

note: amended 2020 to incorporate the Juba Agreement for Peace in Sudan; the military suspended several provisions of the Constitutional Declaration in October 2021

Exchange rates

Exchange rates:

546.759 (2022 est.)

370.791 (2021 est.)

53.996 (2020 est.)

45.767 (2019 est.)

24.329 (2018 est.)

Executive branch

head of government: Sovereign Council Chair and Commander-in-Chief of the Sudanese Armed Forces General Abd-al-Fattah al-BURHAN Abd-al-Rahman (since 11 November 2021)

cabinet: the military forced most members of the Council of Ministers out of office in 2021; a handful of ministers appointed by former armed opposition groups were allowed to retain their posts; at present, most of the members of the Council are appointed senior civil servants serving in an acting-minister capacity

election/appointment process: military members of the Sovereign Council are selected by the leadership of the security forces; representatives of former armed groups to the Sovereign Council are selected by the signatories of the Juba Peace Agreement

election results: NA

expected date of next election: supposed to be held in 2022 or 2023, but the methodology for elections has still not been defined

note 1: the 2019 Constitutional Declaration established a collective chief of state of the "Sovereign Council," which was chaired by al-BURHAN; on 25 October 2021, al-BURHAN dissolved the Sovereign Council but reinstated it on 11 November 2021, replacing its civilian members (previously selected by the umbrella civilian coalition the Forces for Freedom and Change) with civilians of the military’s choosing, but then relieved the newly appointed civilian members of their duties on 6 July 2022

note 2: Sovereign Council currently consists of 5 generals

Flag

meaning: red stands for the struggle for freedom; white for peace, light, and love, black for the people; green for Islam, agriculture, and prosperity

history: colors and design are based on the Arab Revolt flag of World War I

Independence

Industries

Judicial branch

judge selection and term of office: National Supreme Court and Constitutional Court judges selected by the Supreme Judicial Council

subordinate courts: Court of Appeal; other national courts; public courts; district, town, and rural courts

Land boundaries

border countries (7): Central African Republic 174 km; Chad 1,403 km; Egypt 1,276 km; Eritrea 682 km; Ethiopia 744 km; Libya 382 km; South Sudan 2,158 km

note: Sudan-South Sudan boundary represents 1 January 1956 alignment; final alignment pending negotiations and demarcation; final sovereignty status of Abyei region pending negotiations between Sudan and South Sudan

Land use

arable land: 11.2% (2023 est.)

permanent crops: 0.1% (2023 est.)

permanent pasture: 49% (2023 est.)

forest: 12% (2023 est.)

other: 27.7% (2023 est.)

Legal system

Legislative branch

Maritime claims

contiguous zone: 18 nm

continental shelf: 200-m depth or to the depth of exploitation

International organization participation

National holiday

Nationality

adjective: Sudanese

Natural resources

Geography - note

Economic overview

low-income Sahel economy devastated by ongoing civil war; major impacts on rural income, basic commodity prices, industrial production, agricultural supply chain, communications and commerce; hyperinflation and currency depreciation worsening food access and humanitarian conditions

Political parties

Democratic Unionist Party or DUP

Federal Umma Party

Muslim Brotherhood or MB

National Congress Party or NCP

National Umma Party or NUP

Popular Congress Party or PCP

Reform Movement Now

Sudan National Front

Sudanese Communist Party or SCP

Sudanese Congress Party or SCoP

Umma Party for Reform and Development

Unionist Movement Party or UMP

note: in November 2019, the transitional government banned the National Congress Party

Railways

narrow gauge: 5,851 km (2014) 1.067-m gauge

1,400 km 0.600-m gauge for cotton plantations

Suffrage

Terrain

Government type

Country name

conventional short form: Sudan

local long form: Jumhuriyat as-Sudan

local short form: As-Sudan

former: Anglo-Egyptian Sudan, Democratic Republic of the Sudan

etymology: the name derives from the Arabic balad-as-sudan, meaning "Land of the Black [peoples]"

Location

Map references

Irrigated land

Diplomatic representation in the US

chancery: 2210 Massachusetts Avenue NW, Washington, DC 20008

telephone: [1] (202) 338-8565

FAX: [1] (202) 667-2406

email address and website:

consular@sudanembassy.org

https://www.sudanembassy.org/

Internet users

Internet country code

Refugees and internally displaced persons

IDPs: 11,559,970 (2024 est.)

GDP (official exchange rate)

note: data in current dollars at official exchange rate

Trafficking in persons

Total renewable water resources

School life expectancy (primary to tertiary education)

male: 7 years (2015 est.)

female: 7 years (2015 est.)

Urbanization

rate of urbanization: 3.43% annual rate of change (2020-25 est.)

Broadcast media

Drinking water source

urban: 74.2% of population (2022 est.)

rural: 59.7% of population (2022 est.)

total: 64.9% of population (2022 est.)

unimproved:

urban: 25.8% of population (2022 est.)

rural: 40.3% of population (2022 est.)

total: 35.1% of population (2022 est.)

National anthem(s)

lyrics/music: Sayed Ahmad Muhammad SALIH/Ahmad MURJAN

history: adopted 1956; originally served as the anthem of the Sudanese military

Major urban areas - population

International law organization participation

Physician density

Hospital bed density

National symbol(s)

GDP - composition, by end use

government consumption: 16.5% (2024 est.)

investment in fixed capital: 2.9% (2024 est.)

investment in inventories: 0% (2024 est.)

exports of goods and services: 1.2% (2024 est.)

imports of goods and services: -1.3% (2024 est.)

note: figures may not total 100% due to rounding or gaps in data collection

Citizenship

citizenship by descent only: the father must be a citizen of Sudan

dual citizenship recognized: no

residency requirement for naturalization: 10 years

Population distribution

Electricity access

electrification - urban areas: 84%

electrification - rural areas: 49.4%

Civil aircraft registration country code prefix

Ethnic groups

Religions

Languages

major-language sample(s):

كتاب حقائق العالم، المصدر الذي لا يمكن الاستغناء عنه للمعلومات الأساسية (Arabic)

The World Factbook, the indispensable source for basic information. (English)

Imports - partners

note: top five import partners based on percentage share of imports

Elevation

lowest point: Red Sea 0 m

mean elevation: 568 m

Health expenditure

6.7% of national budget (2022 est.)

Military - note

the Sudanese military has been a dominant force in the ruling of the country since its independence in 1956; in addition, the military has a large role in the country's economy, reportedly controlling over 200 commercial companies, including businesses involved in gold mining, rubber production, agriculture, and meat exports

the UN Interim Security Force for Abyei (UNISFA) has operated in the disputed Abyei region along the border between Sudan and South Sudan since 2011; UNISFA's mission includes ensuring security, protecting civilians, strengthening the capacity of the Abyei Police Service, de-mining, monitoring/verifying the redeployment of armed forces from the area, and facilitating the flow of humanitarian aid; as of 2025, UNISFA had approximately 3,800 personnel assigned (2025)

Military and security service personnel strengths

Military equipment inventories and acquisitions

note 1: Sudan has been under a UN Security Council approved arms embargo since 2005 as a result of violence in Darfur; in September 2025, the embargo was extended for another year

note 2: the RSF traditionally has been a lightly armed paramilitary force but over the years is reported to have acquired some heavier armaments such as armored vehicles, artillery, and anti-aircraft guns; it has captured some SAF arms and equipment during the ongoing conflict; since the start of the conflict, both the RSF and the SAF are reported to have received additional weaponry from various foreign suppliers

Total water withdrawal

industrial: 75 million cubic meters (2022 est.)

agricultural: 25.91 billion cubic meters (2022 est.)

Waste and recycling

percent of municipal solid waste recycled: 8.9% (2022 est.)

Terrorist group(s)

note: details about the history, aims, leadership, organization, areas of operation, tactics, targets, weapons, size, and sources of support of the group(s) appear(s) in the Terrorism reference guide

Major aquifers

Major watersheds (area sq km)

Internal (endorheic basin) drainage: Lake Chad (2,497,738 sq km)

Major rivers (by length in km)

note: [s] after country name indicates river source; [m] after country name indicates river mouth

National heritage

selected World Heritage Site locales: Gebel Barkal and the Sites of the Napatan Region (c); Archaeological Sites of the Island of Meroe (c); Sanganeb Marine National Park and Dungonab Bay – Mukkawar Island Marine National Park (n)

Coal

imports: 200 metric tons (2023 est.)

Electricity generation sources

solar: 0.8% of total installed capacity (2023 est.)

hydroelectricity: 68.7% of total installed capacity (2023 est.)

biomass and waste: 0.6% of total installed capacity (2023 est.)

Natural gas

Petroleum

refined petroleum consumption: 129,000 bbl/day (2023 est.)

crude oil estimated reserves: 1.25 billion barrels (2021 est.)

Gross reproduction rate

Remittances

2.9% of GDP (2022 est.)

3.3% of GDP (2021 est.)

note: personal transfers and compensation between resident and non-resident individuals/households/entities

Ports

large: 0

medium: 2

small: 2

very small: 0

ports with oil terminals: 3

key ports: Al Khair Oil Terminal, Beshayer Oil Terminal, Port Sudan, Sawakin Harbor

National color(s)

Particulate matter emissions

Methane emissions

agriculture: 1,509.6 kt (2019-2021 est.)

waste: 198.7 kt (2019-2021 est.)

other: 38.8 kt (2019-2021 est.)

Labor force

note: number of people ages 15 or older who are employed or seeking work

Youth unemployment rate (ages 15-24)

male: 11.8% (2022 est.)

female: 13.1% (2022 est.)

note: % of labor force ages 15-24 seeking employment

Net migration rate

Median age

male: 19 years

female: 19.6 years

Debt - external

note: present value of external debt in current US dollars

Maternal mortality ratio

Reserves of foreign exchange and gold

$168.284 million (2016 est.)

$173.516 million (2015 est.)

note: holdings of gold (year-end prices)/foreign exchange/special drawing rights in current dollars

Total fertility rate

Unemployment rate

7.6% (2022 est.)

11.1% (2021 est.)

note: % of labor force seeking employment

Carbon dioxide emissions

from coal and metallurgical coke: 300 metric tonnes of CO2 (2023 est.)

from petroleum and other liquids: 18.242 million metric tonnes of CO2 (2023 est.)

Area

land: 1,731,671 sq km

water: 129,813 sq km

Taxes and other revenues

note: central government tax revenue as a % of GDP

Real GDP (purchasing power parity)

$109.147 billion (2023 est.)

$154.672 billion (2022 est.)

note: data in 2021 dollars

Airports

Infant mortality rate

male: 46 deaths/1,000 live births

female: 34.8 deaths/1,000 live births

Inflation rate (consumer prices)

359.1% (2021 est.)

163.3% (2020 est.)

note: annual % change based on consumer prices

Current account balance

-$2.62 billion (2021 est.)

-$5.841 billion (2020 est.)

note: balance of payments - net trade and primary/secondary income in current dollars

Real GDP per capita

$2,200 (2023 est.)

$3,100 (2022 est.)

note: data in 2021 dollars

Broadband - fixed subscriptions

subscriptions per 100 inhabitants: (2022 est.) less than 1

Obesity - adult prevalence rate

Energy consumption per capita

Death rate

Birth rate

Electricity

consumption: 13.983 billion kWh (2023 est.)

imports: 882 million kWh (2023 est.)

transmission/distribution losses: 3.646 billion kWh (2023 est.)

Merchant marine

by type: other 14

Children under the age of 5 years underweight

Imports

$10.271 billion (2021 est.)

$10.52 billion (2020 est.)

note: balance of payments - imports of goods and services in current dollars

Exports

$6.664 billion (2021 est.)

$5.065 billion (2020 est.)

note: balance of payments - exports of goods and services in current dollars

Heliports

Telephones - fixed lines

subscriptions per 100 inhabitants: (2022 est.) less than 1

Alcohol consumption per capita

beer: 0 liters of pure alcohol (2019 est.)

wine: 0 liters of pure alcohol (2019 est.)

spirits: 0.29 liters of pure alcohol (2019 est.)

other alcohols: 1.63 liters of pure alcohol (2019 est.)

Life expectancy at birth

male: 65.5 years

female: 70.2 years

Real GDP growth rate

-29.4% (2023 est.)

-1% (2022 est.)

note: annual GDP % growth based on constant local currency

Industrial production growth rate

note: annual % change in industrial value added based on constant local currency

GDP - composition, by sector of origin

industry: 23% (2024 est.)

services: 54.9% (2024 est.)

note: figures may not total 100% due to non-allocated consumption not captured in sector-reported data

Population growth rate

Military service age and obligation

note: official implementation of compulsory service is reportedly uneven; both the SAF and the RSF have been accused of engaging in forced recruitment of men and boys during the ongoing conflict

Dependency ratios

youth dependency ratio: 69.8 (2025 est.)

elderly dependency ratio: 5.8 (2025 est.)

potential support ratio: 17.2 (2025 est.)

Population

male: 25,981,767

female: 25,785,670

Telephones - mobile cellular

subscriptions per 100 inhabitants: 70 (2022 est.)