Myanmar - MM - MMR - MYA - East and Southeast Asia

Last updated: January 05, 2026

Burma Images

Burma Factbook Data

Diplomatic representation from the US

chief of mission: Ambassador (vacant); Chargé d’Affaires Susan STEVENSON (since 10 July 2023)

embassy: 110 University Avenue, Kamayut Township, Rangoon

mailing address: 4250 Rangoon Place, Washington DC 20521-4250

telephone: [95] (1) 753-6509

FAX: [95] (1) 751-1069

email address and website:

ACSRangoon@state.gov

https://mm.usembassy.gov/

embassy: 110 University Avenue, Kamayut Township, Rangoon

mailing address: 4250 Rangoon Place, Washington DC 20521-4250

telephone: [95] (1) 753-6509

FAX: [95] (1) 751-1069

email address and website:

ACSRangoon@state.gov

https://mm.usembassy.gov/

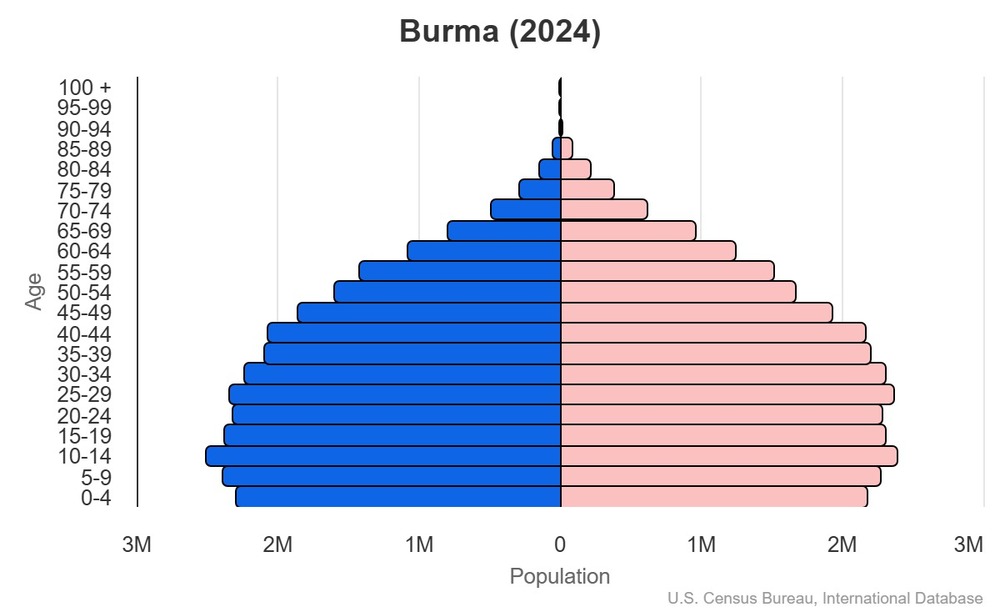

Age structure

0-14 years: 24.4% (male 7,197,177/female 6,843,879)

15-64 years: 68.5% (male 19,420,361/female 19,998,625)

65 years and over: 7.1% (2024 est.) (male 1,770,293/female 2,296,804)

15-64 years: 68.5% (male 19,420,361/female 19,998,625)

65 years and over: 7.1% (2024 est.) (male 1,770,293/female 2,296,804)

This is the population pyramid for Burma. A population pyramid illustrates the age and sex structure of a country's population and may provide insights about political and social stability, as well as economic development. The population is distributed along the horizontal axis, with males shown on the left and females on the right. The male and female populations are broken down into 5-year age groups represented as horizontal bars along the vertical axis, with the youngest age groups at the bottom and the oldest at the top. The shape of the population pyramid gradually evolves over time based on fertility, mortality, and international migration trends.

For additional information, please see the entry for Population pyramid on the Definitions and Notes page.

For additional information, please see the entry for Population pyramid on the Definitions and Notes page.

Geographic coordinates

22 00 N, 98 00 E

Sex ratio

at birth: 1.06 male(s)/female

0-14 years: 1.05 male(s)/female

15-64 years: 0.97 male(s)/female

65 years and over: 0.77 male(s)/female

total population: 0.97 male(s)/female (2024 est.)

0-14 years: 1.05 male(s)/female

15-64 years: 0.97 male(s)/female

65 years and over: 0.77 male(s)/female

total population: 0.97 male(s)/female (2024 est.)

Natural hazards

destructive earthquakes and cyclones; flooding and landslides common during rainy season (June to September); periodic droughts

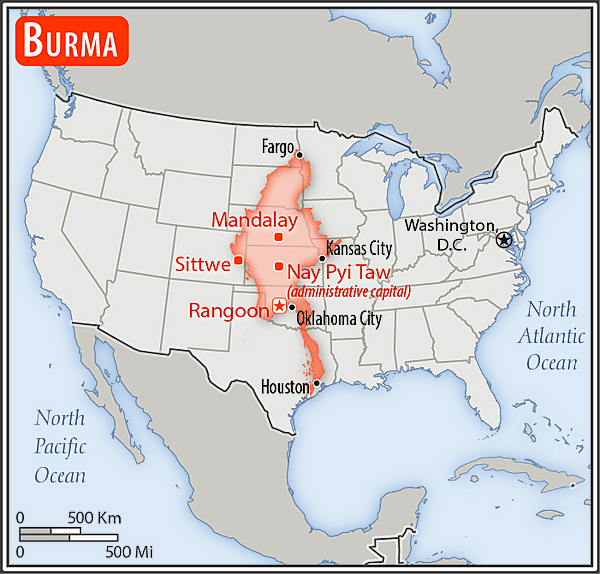

Area - comparative

slightly smaller than Texas

slightly smaller than Texas

Background

Burma is home to ethnic Burmans and scores of other ethnic and religious minority groups that have resisted external efforts to consolidate control of the country throughout its history. Britain conquered Burma over a period extending from the 1820s to the 1880s and administered it as a province of India until 1937, when Burma became a self-governing colony. Burma gained full independence in 1948. In 1962, General NE WIN seized power and ruled the country until 1988 when a new military regime took control.

In 1990, the military regime permitted an election but then rejected the results after the main opposition National League for Democracy (NLD) and its leader AUNG SAN SUU KYI (ASSK) won in a landslide. The military regime placed ASSK under house arrest until 2010. In 2007, rising fuel prices in Burma led pro-democracy activists and Buddhist monks to launch a "Saffron Revolution" consisting of large protests against the regime, which violently suppressed the movement. The regime prevented new elections until it had drafted a constitution designed to preserve the military's political control; it passed the new constitution in its 2008 referendum. The regime conducted an election in 2010, but the NLD boycotted the vote, and the military’s political proxy, the Union Solidarity and Development Party, easily won; international observers denounced the election as flawed.

Burma nonetheless began a halting process of political and economic reforms. ASSK's return to government in 2012 eventually led to the NLD's sweeping victory in the 2015 election. With ASSK as the de facto head of state, Burma’s first credibly elected civilian government drew international criticism for blocking investigations into Burma’s military operations -- which the US Department of State determined constituted genocide -- against its ethnic Rohingya population. When the 2020 elections resulted in further NLD gains, the military denounced the vote as fraudulent. In 2021, the military's senior leader General MIN AUNG HLAING launched a coup that returned Burma to authoritarian rule, with military crackdowns that undid reforms and resulted in the detention of ASSK and thousands of pro-democracy actors.

Pro-democracy organizations have formed in the wake of the coup, including the National Unity Government (NUG). Members of the NUG include representatives from the NLD, ethnic minority groups, and civil society. In 2021, the NUG announced the formation of armed militias called the People's Defense Forces (PDF) and an insurgency against the military junta. As of 2024, PDF units across the country continued to fight the regime with varying levels of support from and cooperation with the NUG and other anti-regime organizations, including armed ethnic groups that have been fighting the central government for decades.

In 1990, the military regime permitted an election but then rejected the results after the main opposition National League for Democracy (NLD) and its leader AUNG SAN SUU KYI (ASSK) won in a landslide. The military regime placed ASSK under house arrest until 2010. In 2007, rising fuel prices in Burma led pro-democracy activists and Buddhist monks to launch a "Saffron Revolution" consisting of large protests against the regime, which violently suppressed the movement. The regime prevented new elections until it had drafted a constitution designed to preserve the military's political control; it passed the new constitution in its 2008 referendum. The regime conducted an election in 2010, but the NLD boycotted the vote, and the military’s political proxy, the Union Solidarity and Development Party, easily won; international observers denounced the election as flawed.

Burma nonetheless began a halting process of political and economic reforms. ASSK's return to government in 2012 eventually led to the NLD's sweeping victory in the 2015 election. With ASSK as the de facto head of state, Burma’s first credibly elected civilian government drew international criticism for blocking investigations into Burma’s military operations -- which the US Department of State determined constituted genocide -- against its ethnic Rohingya population. When the 2020 elections resulted in further NLD gains, the military denounced the vote as fraudulent. In 2021, the military's senior leader General MIN AUNG HLAING launched a coup that returned Burma to authoritarian rule, with military crackdowns that undid reforms and resulted in the detention of ASSK and thousands of pro-democracy actors.

Pro-democracy organizations have formed in the wake of the coup, including the National Unity Government (NUG). Members of the NUG include representatives from the NLD, ethnic minority groups, and civil society. In 2021, the NUG announced the formation of armed militias called the People's Defense Forces (PDF) and an insurgency against the military junta. As of 2024, PDF units across the country continued to fight the regime with varying levels of support from and cooperation with the NUG and other anti-regime organizations, including armed ethnic groups that have been fighting the central government for decades.

Environmental issues

deforestation; industrial pollution of air, soil, and water; inadequate sanitation and water treatment; rapid depletion of the country's natural resources

International environmental agreements

party to: Biodiversity, Climate Change, Climate Change-Kyoto Protocol, Climate Change-Paris Agreement, Comprehensive Nuclear Test Ban, Desertification, Endangered Species, Hazardous Wastes, Law of the Sea, Nuclear Test Ban, Ozone Layer Protection, Ship Pollution, Tropical Timber 2006, Wetlands

signed, but not ratified: none of the selected agreements

signed, but not ratified: none of the selected agreements

Military expenditures

3.9% of GDP (2023 est.)

3.6% of GDP (2022 est.)

3.5% of GDP (2021 est.)

3% of GDP (2020 est.)

4.1% of GDP (2019 est.)

3.6% of GDP (2022 est.)

3.5% of GDP (2021 est.)

3% of GDP (2020 est.)

4.1% of GDP (2019 est.)

Population below poverty line

24.8% (2017 est.)

note: % of population with income below national poverty line

note: % of population with income below national poverty line

Household income or consumption by percentage share

lowest 10%: 3.8% (2017 est.)

highest 10%: 25.5% (2017 est.)

note: % share of income accruing to lowest and highest 10% of population

highest 10%: 25.5% (2017 est.)

note: % share of income accruing to lowest and highest 10% of population

Exports - commodities

garments, natural gas, dried legumes, rare-earth metal compounds, precious stones (2023)

note: top five export commodities based on value in dollars

note: top five export commodities based on value in dollars

Exports - partners

China 32%, Thailand 16%, Japan 7%, Germany 6%, India 5% (2023)

note: top five export partners based on percentage share of exports

note: top five export partners based on percentage share of exports

Administrative divisions

7 regions (taing-myar, singular - taing), 7 states (pyi ne-myar, singular - pyi ne), 1 union territory

regions: Ayeyarwady (Irrawaddy), Bago, Magway, Mandalay, Sagaing, Tanintharyi, Yangon (Rangoon)

states: Chin, Kachin, Kayah, Karen, Mon, Rakhine, Shan

union territory: Nay Pyi Taw

regions: Ayeyarwady (Irrawaddy), Bago, Magway, Mandalay, Sagaing, Tanintharyi, Yangon (Rangoon)

states: Chin, Kachin, Kayah, Karen, Mon, Rakhine, Shan

union territory: Nay Pyi Taw

Agricultural products

rice, sugarcane, vegetables, beans, maize, groundnuts, plantains, fruits, coconuts, onions (2023)

note: top ten agricultural products based on tonnage

note: top ten agricultural products based on tonnage

Military and security forces

Burmese Defense Service (aka Armed Forces of Burma, Myanmar Army, Royal Armed Forces, the Tatmadaw, or the Sit-Tat): Army (Tatmadaw Kyi), Navy (Tatmadaw Yay), Air Force (Tatmadaw Lay); People’s Militia

Ministry of Home Affairs: Burma (People's) Police Force, Border Guard Forces/Police (2025)

note 1: under the 2008 constitution, the Tatmadaw was given control over the appointments of senior officials to lead the Ministry of Defense, the Ministry of Border Affairs, and the Ministry of Home Affairs; in 2022, a new law gave the commander-in-chief of the Tatmadaw the authority to appoint or remove the head of the police force

note 2: the military is supported by pro-government militias; some are integrated within the Tatmadaw’s command structure as Border Guard Forces, which are organized as battalions with a mix of militia forces, ethnic armed groups, and government soldiers that are armed, supplied, and paid by the Tatmadaw; other pro-military government militias are not integrated within the Tatmadaw command structure but receive direction and some support from the military and are recognized as government militias; a third type of pro-government militias are small community-based units that are armed, coordinated, and trained by local Tatmadaw forces and activated as needed

Ministry of Home Affairs: Burma (People's) Police Force, Border Guard Forces/Police (2025)

note 1: under the 2008 constitution, the Tatmadaw was given control over the appointments of senior officials to lead the Ministry of Defense, the Ministry of Border Affairs, and the Ministry of Home Affairs; in 2022, a new law gave the commander-in-chief of the Tatmadaw the authority to appoint or remove the head of the police force

note 2: the military is supported by pro-government militias; some are integrated within the Tatmadaw’s command structure as Border Guard Forces, which are organized as battalions with a mix of militia forces, ethnic armed groups, and government soldiers that are armed, supplied, and paid by the Tatmadaw; other pro-military government militias are not integrated within the Tatmadaw command structure but receive direction and some support from the military and are recognized as government militias; a third type of pro-government militias are small community-based units that are armed, coordinated, and trained by local Tatmadaw forces and activated as needed

Budget

revenues: $10.945 billion (2019 est.)

expenditures: $10.22 billion (2019 est.)

note: central government revenues (excluding grants) and expenses converted to US dollars at average official exchange rate for year indicated

expenditures: $10.22 billion (2019 est.)

note: central government revenues (excluding grants) and expenses converted to US dollars at average official exchange rate for year indicated

Capital

name: Rangoon (aka Yangon, continues to be recognized as the primary Burmese capital by the US Government); Nay Pyi Taw is the administrative capital

geographic coordinates: 16 48 N, 96 10 E

time difference: UTC+6.5 (11.5 hours ahead of Washington, DC, during Standard Time)

etymology: Rangoon/Yangon derives from the Burmese words yan and koun, commonly translated as "end of strife"; Nay Pyi Taw translates as "abode of kings"

geographic coordinates: 16 48 N, 96 10 E

time difference: UTC+6.5 (11.5 hours ahead of Washington, DC, during Standard Time)

etymology: Rangoon/Yangon derives from the Burmese words yan and koun, commonly translated as "end of strife"; Nay Pyi Taw translates as "abode of kings"

Imports - commodities

refined petroleum, synthetic fabric, fertilizers, crude petroleum, fabric (2023)

note: top five import commodities based on value in dollars

note: top five import commodities based on value in dollars

Climate

tropical monsoon; cloudy, rainy, hot, humid summers (southwest monsoon, June to September); less cloudy, scant rainfall, mild temperatures, lower humidity during winter (northeast monsoon, December to April)

Coastline

1,930 km

Constitution

history: previous 1947, 1974 (suspended until 2008); latest drafted 9 April 2008, approved by referendum 29 May 2008

amendment process: proposals require at least 20% approval by the Assembly of the Union membership; passage of amendments to sections of the constitution on basic principles, government structure, branches of government, state emergencies, and amendment procedures requires 75% approval by the Assembly and approval in a referendum by absolute majority of registered voters; passage of amendments to other sections requires only 75% Assembly approval; military granted 25% of parliamentary seats by default

amendment process: proposals require at least 20% approval by the Assembly of the Union membership; passage of amendments to sections of the constitution on basic principles, government structure, branches of government, state emergencies, and amendment procedures requires 75% approval by the Assembly and approval in a referendum by absolute majority of registered voters; passage of amendments to other sections requires only 75% Assembly approval; military granted 25% of parliamentary seats by default

Exchange rates

kyats (MMK) per US dollar -

Exchange rates:

2,100 (2023 est.)

1,932.543 (2022 est.)

1,615.367 (2021 est.)

1,381.619 (2020 est.)

1,518.255 (2019 est.)

Exchange rates:

2,100 (2023 est.)

1,932.543 (2022 est.)

1,615.367 (2021 est.)

1,381.619 (2020 est.)

1,518.255 (2019 est.)

Executive branch

chief of state: Acting President Sr. Gen. MIN AUNG HLAING (since 31 July 2025)

head of government: Prime Minister NYO SAW (since 31 July 2025)

cabinet: Cabinet appointments shared by the president and the commander-in-chief

election/appointment process: prior to the military takeover in 2021, president was indirectly elected by simple majority vote by the full Assembly of the Union from among 3 vice-presidential candidates nominated by the Presidential Electoral College (consists of members of the lower and upper houses and military members); the other 2 candidates became vice presidents (president elected for a 5-year term)

most recent election date: 8 November 2020

election results:

2020: the National League for Democracy (NLD) won 396 seats across both houses -- well above the 322 required for a parliamentary majority -- but on 1 February 2021, the military claimed the results of the election were illegitimate and deposed State Counsellor AUNG SAN SUU KYI and President WIN MYINT of the NLD, causing military-affiliated Vice President MYINT SWE (USDP) to become acting president; MYINT SWE subsequently handed power to coup leader MIN AUNG HLAING; WIN MYINT and other key leaders of the ruling NLD party were placed under arrest after the military takeover

2018: WIN MYINT elected president in an indirect by-election held on 28 March 2018 after the resignation of HTIN KYAW; Assembly of the Union vote for president - WIN MYINT (NLD) 403, MYINT SWE (USDP) 211, HENRY VAN THIO (NLD) 18, 4 votes canceled (636 votes cast)

expected date of next election: on 31 July 2025, the military government announced that it was preparing for elections to be held in December 2025

state counsellor: State Counselor AUNG SAN SUU KYI (since 6 April 2016); note - under arrest since 1 February 2021

note 1: on 31 July 2025, the military ended the state of emergency that had been in place since taking over the government in February 2021, although martial law continues to exist in parts of the country; at the same time, the military dissolved the State Administrative Council (SAC), which had been the official name of the military government in Burma, and replaced it with the National Security and Peace Commission (NSPC), chaired by Sr. Gen. MIN AUNG HLAING, who also retains his position as chief of the armed forces

note 2: prior to the military takeover, the state counsellor served the equivalent term of the president and was similar to a prime minister

head of government: Prime Minister NYO SAW (since 31 July 2025)

cabinet: Cabinet appointments shared by the president and the commander-in-chief

election/appointment process: prior to the military takeover in 2021, president was indirectly elected by simple majority vote by the full Assembly of the Union from among 3 vice-presidential candidates nominated by the Presidential Electoral College (consists of members of the lower and upper houses and military members); the other 2 candidates became vice presidents (president elected for a 5-year term)

most recent election date: 8 November 2020

election results:

2020: the National League for Democracy (NLD) won 396 seats across both houses -- well above the 322 required for a parliamentary majority -- but on 1 February 2021, the military claimed the results of the election were illegitimate and deposed State Counsellor AUNG SAN SUU KYI and President WIN MYINT of the NLD, causing military-affiliated Vice President MYINT SWE (USDP) to become acting president; MYINT SWE subsequently handed power to coup leader MIN AUNG HLAING; WIN MYINT and other key leaders of the ruling NLD party were placed under arrest after the military takeover

2018: WIN MYINT elected president in an indirect by-election held on 28 March 2018 after the resignation of HTIN KYAW; Assembly of the Union vote for president - WIN MYINT (NLD) 403, MYINT SWE (USDP) 211, HENRY VAN THIO (NLD) 18, 4 votes canceled (636 votes cast)

expected date of next election: on 31 July 2025, the military government announced that it was preparing for elections to be held in December 2025

state counsellor: State Counselor AUNG SAN SUU KYI (since 6 April 2016); note - under arrest since 1 February 2021

note 1: on 31 July 2025, the military ended the state of emergency that had been in place since taking over the government in February 2021, although martial law continues to exist in parts of the country; at the same time, the military dissolved the State Administrative Council (SAC), which had been the official name of the military government in Burma, and replaced it with the National Security and Peace Commission (NSPC), chaired by Sr. Gen. MIN AUNG HLAING, who also retains his position as chief of the armed forces

note 2: prior to the military takeover, the state counsellor served the equivalent term of the president and was similar to a prime minister

Flag

description: three equal horizontal stripes of yellow (top), green, and red; centered on the green band is a five-pointed white star that overlaps onto the yellow and red stripes

history: the design revives the triband colors that Burma used from 1943 to 1945, during the Japanese occupation

history: the design revives the triband colors that Burma used from 1943 to 1945, during the Japanese occupation

Illicit drugs

USG identification:

major illicit drug-producing and/or drug-transit country

major precursor-chemical producer (2025)

major illicit drug-producing and/or drug-transit country

major precursor-chemical producer (2025)

Independence

4 January 1948 (from the UK)

Industries

agricultural processing; wood and wood products; copper, tin, tungsten, iron; cement, construction materials; pharmaceuticals; fertilizer; oil and natural gas; garments; jade and gems

Judicial branch

highest court(s): Supreme Court of the Union (consists of the chief justice and 7-11 judges)

judge selection and term of office: chief justice and judges nominated by the president, with approval of the Lower House, and appointed by the president; judges normally serve until mandatory retirement at age 70

subordinate courts: High Courts of the Region; High Courts of the State; Court of the Self-Administered Division; Court of the Self-Administered Zone; district and township courts; special courts (for juvenile, municipal, and traffic offenses); courts martial

judge selection and term of office: chief justice and judges nominated by the president, with approval of the Lower House, and appointed by the president; judges normally serve until mandatory retirement at age 70

subordinate courts: High Courts of the Region; High Courts of the State; Court of the Self-Administered Division; Court of the Self-Administered Zone; district and township courts; special courts (for juvenile, municipal, and traffic offenses); courts martial

Land boundaries

total: 6,522 km

border countries (5): Bangladesh 271 km; China 2,129 km; India 1,468 km; Laos 238 km; Thailand 2,416 km

border countries (5): Bangladesh 271 km; China 2,129 km; India 1,468 km; Laos 238 km; Thailand 2,416 km

Land use

agricultural land: 19.9% (2023 est.)

arable land: 16.9% (2023 est.)

permanent crops: 2.3% (2023 est.)

permanent pasture: 0.7% (2023 est.)

forest: 42.4% (2023 est.)

other: 37.7% (2023 est.)

arable land: 16.9% (2023 est.)

permanent crops: 2.3% (2023 est.)

permanent pasture: 0.7% (2023 est.)

forest: 42.4% (2023 est.)

other: 37.7% (2023 est.)

Legal system

mixed legal system of English common law (as introduced in codifications designed for colonial India) and customary law

Literacy

total population: 93.5% (2020 est.)

male: 94.7% (2020 est.)

female: 92.7% (2020 est.)

male: 94.7% (2020 est.)

female: 92.7% (2020 est.)

Maritime claims

territorial sea: 12 nm

contiguous zone: 24 nm

exclusive economic zone: 200 nm

continental shelf: 200 nm or to the edge of the continental margin

contiguous zone: 24 nm

exclusive economic zone: 200 nm

continental shelf: 200 nm or to the edge of the continental margin

International organization participation

ADB, ARF, ASEAN, BIMSTEC, CP, EAS, EITI (candidate country), FAO, G-77, IAEA, IBRD, ICAO, ICRM, IDA, IFAD, IFC, IFRCS, IHO, ILO, IMF, IMO, Interpol, IOC, IOM, IPU, ISO (correspondent), ITU, ITUC (NGOs), NAM, OPCW (signatory), SAARC (observer), UN, UNCTAD, UNESCO, UNIDO, UNWTO, UPU, WCO, WHO, WIPO, WMO, WTO

National holiday

Independence Day, 4 January (1948); Union Day, 12 February (1947)

Nationality

noun: Burmese (singular and plural)

adjective: Burmese

adjective: Burmese

Natural resources

petroleum, timber, tin, antimony, zinc, copper, tungsten, lead, coal, marble, limestone, precious stones, natural gas, hydropower, arable land

Geography - note

strategic location near major Indian Ocean shipping lanes; the north-south flowing Irrawaddy River is the country's largest and most important commercial waterway

Economic overview

prior to COVID-19 and the February 2021 military coup, massive declines in poverty, rapid economic growth, and improving social welfare; underdevelopment, climate change, and unequal investment threaten progress and sustainability planning; since coup, foreign assistance has ceased from most funding sources

Railways

total: 5,031 km (2008)

narrow gauge: 5,031 km (2008) 1.000-m gauge

narrow gauge: 5,031 km (2008) 1.000-m gauge

Suffrage

18 years of age; universal

Terrain

central lowlands ringed by steep, rugged highlands

Government type

military regime

Country name

conventional long form: Union of Burma

conventional short form: Burma

local long form: Pyidaungzu Thammada Myanma Naingngandaw (translated as the Republic of the Union of Myanmar)

local short form: Myanma Naingngandaw

former: Socialist Republic of the Union of Burma, Union of Myanmar

etymology: both "Burma" and "Myanmar" derive from the name of the majority Burman (Bamar) ethnic group, with the term myanma, or "the strong," being the group's name for itself

note: since 1989 the military authorities in Burma and the deposed parliamentary government have promoted the name Myanmar as a conventional name for their state; the US Government has not officially adopted the name

conventional short form: Burma

local long form: Pyidaungzu Thammada Myanma Naingngandaw (translated as the Republic of the Union of Myanmar)

local short form: Myanma Naingngandaw

former: Socialist Republic of the Union of Burma, Union of Myanmar

etymology: both "Burma" and "Myanmar" derive from the name of the majority Burman (Bamar) ethnic group, with the term myanma, or "the strong," being the group's name for itself

note: since 1989 the military authorities in Burma and the deposed parliamentary government have promoted the name Myanmar as a conventional name for their state; the US Government has not officially adopted the name

Location

Southeastern Asia, bordering the Andaman Sea and the Bay of Bengal, between Bangladesh and Thailand

Map references

Southeast Asia

Irrigated land

17,140 sq km (2020)

Diplomatic representation in the US

chief of mission: Ambassador (vacant); Chargé d'Affaires Soe Thet NAUNG (since 24 June 2025)

chancery: 2300 S Street NW, Washington, DC 20008

telephone: [1] (202) 332-3344

FAX: [1] (202) 332-4351

email address and website:

washington-embassy@mofa.gov.mm

https://www.mewashingtondc.org/

consulate(s) general: Los Angeles

chancery: 2300 S Street NW, Washington, DC 20008

telephone: [1] (202) 332-3344

FAX: [1] (202) 332-4351

email address and website:

washington-embassy@mofa.gov.mm

https://www.mewashingtondc.org/

consulate(s) general: Los Angeles

Internet users

percent of population: 59% (2023 est.)

Internet country code

.mm

Refugees and internally displaced persons

IDPs: 3,646,658 (2024 est.)

stateless persons: 619,429 (2024 est.)

stateless persons: 619,429 (2024 est.)

GDP (official exchange rate)

$74.08 billion (2024 est.)

note: data in current dollars at official exchange rate

note: data in current dollars at official exchange rate

Trafficking in persons

tier rating: Tier 3 — Burma does not fully meet the minimum standards for the elimination of trafficking and is not making significant efforts to do so, therefore, Burma remained on Tier 3; for more details, go to: https://www.state.gov/reports/2025-trafficking-in-persons-report/burma/

Total renewable water resources

1.168 trillion cubic meters (2022 est.)

School life expectancy (primary to tertiary education)

total: 12 years (2018 est.)

male: 11 years (2018 est.)

female: 12 years (2018 est.)

male: 11 years (2018 est.)

female: 12 years (2018 est.)

Urbanization

urban population: 32.1% of total population (2023)

rate of urbanization: 1.85% annual rate of change (2020-25 est.)

rate of urbanization: 1.85% annual rate of change (2020-25 est.)

Broadcast media

government controls all domestic broadcast media; 2 state-controlled TV stations, with 1 controlled by the armed forces; 2 pay-TV stations are joint state-private ventures; 1 state-controlled radio station; 9 FM stations are joint state-private ventures; several international broadcasts are available in some areas; the Voice of America (VOA), Radio Free Asia (RFA), BBC Burmese service, the Democratic Voice of Burma (DVB), and Radio Australia use shortwave to broadcast; VOA, RFA, and DVB produce daily TV news programs that are transmitted by satellite; in 2017, the government granted licenses to 5 private broadcasters for digital free-to-air TV channels to be operated in partnership with government-owned Myanmar Radio and Television (MRTV); after the 2021 military coup, the regime revoked the media licenses of most independent outlets, including the free-to-air licenses for DVB and Mizzima (2022)

Drinking water source

improved:

urban: 93.7% of population (2022 est.)

rural: 77.1% of population (2022 est.)

total: 82.4% of population (2022 est.)

unimproved:

urban: 6.3% of population (2022 est.)

rural: 22.9% of population (2022 est.)

total: 17.6% of population (2022 est.)

urban: 93.7% of population (2022 est.)

rural: 77.1% of population (2022 est.)

total: 82.4% of population (2022 est.)

unimproved:

urban: 6.3% of population (2022 est.)

rural: 22.9% of population (2022 est.)

total: 17.6% of population (2022 est.)

National anthem(s)

title: "Kaba Ma Kyei" (Till the End of the World)

lyrics/music: SAYA TIN

history: adopted 1948

lyrics/music: SAYA TIN

history: adopted 1948

This is an audio of the National Anthem for Burma. The national anthem is generally a patriotic musical composition - usually in the form of a song or hymn of praise - that evokes and eulogizes the history, traditions, or struggles of a nation or its people. National anthems can be officially recognized as a national song by a country's constitution or by an enacted law, or simply by tradition. Although most anthems contain lyrics, some do not.

Major urban areas - population

5.610 million RANGOON (Yangon) (capital), 1.532 million Mandalay (2023)

International law organization participation

has not submitted an ICJ jurisdiction declaration; non-party state to the ICCt

Physician density

0.76 physicians/1,000 population (2019)

Hospital bed density

1.1 beds/1,000 population (2020 est.)

National symbol(s)

chinthe (mythical lion)

Mother's mean age at first birth

24.7 years (2015/16 est.)

note: data represents median age at first birth among women 25-49

note: data represents median age at first birth among women 25-49

Dependency ratios

total dependency ratio: 45.9 (2024 est.)

youth dependency ratio: 35.6 (2024 est.)

elderly dependency ratio: 10.3 (2024 est.)

potential support ratio: 9.7 (2024 est.)

youth dependency ratio: 35.6 (2024 est.)

elderly dependency ratio: 10.3 (2024 est.)

potential support ratio: 9.7 (2024 est.)

Citizenship

citizenship by birth: no

citizenship by descent only: both parents must be citizens of Burma

dual citizenship recognized: no

residency requirement for naturalization: none

note: an applicant for naturalization must be the child or spouse of a citizen

citizenship by descent only: both parents must be citizens of Burma

dual citizenship recognized: no

residency requirement for naturalization: none

note: an applicant for naturalization must be the child or spouse of a citizen

Population distribution

population concentrated along coastal areas and in general proximity to the shores of the Irrawaddy River; the extreme north is relatively underpopulated

Electricity access

electrification - total population: 73.7% (2022 est.)

electrification - urban areas: 93.9%

electrification - rural areas: 62.8%

electrification - urban areas: 93.9%

electrification - rural areas: 62.8%

Civil aircraft registration country code prefix

XY

Sanitation facility access

improved:

urban: 94.1% of population (2022 est.)

rural: 82% of population (2022 est.)

total: 85.9% of population (2022 est.)

unimproved:

urban: 5.9% of population (2022 est.)

rural: 18% of population (2022 est.)

total: 14.1% of population (2022 est.)

urban: 94.1% of population (2022 est.)

rural: 82% of population (2022 est.)

total: 85.9% of population (2022 est.)

unimproved:

urban: 5.9% of population (2022 est.)

rural: 18% of population (2022 est.)

total: 14.1% of population (2022 est.)

Ethnic groups

Burman (Bamar) 68%, Shan 9%, Karen 7%, Rakhine 4%, Chinese 3%, Indian 2%, Mon 2%, other 5%

note: the largest ethnic group — the Burman (or Bamar) — dominate politics, and the military ranks are largely drawn from this ethnic group; the Burman mainly populate the central parts of the country, while various ethnic minorities have traditionally lived in the peripheral regions that surround the plains in a horseshoe shape; the government recognizes 135 indigenous ethnic groups

note: the largest ethnic group — the Burman (or Bamar) — dominate politics, and the military ranks are largely drawn from this ethnic group; the Burman mainly populate the central parts of the country, while various ethnic minorities have traditionally lived in the peripheral regions that surround the plains in a horseshoe shape; the government recognizes 135 indigenous ethnic groups

Religions

Buddhist 87.9%, Christian 6.2%, Muslim 4.3%, Animist 0.8%, Hindu 0.5%, other 0.2%, none 0.1% (2014 est.)

note: religion estimate is based on the 2014 national census, including an estimate for the non-enumerated population of Rakhine State, which is assumed to mainly affiliate with the Islamic faith; as of December 2019, Muslims probably make up less than 3% of Burma's total population due to the large outmigration of the Rohingya population since 2017

note: religion estimate is based on the 2014 national census, including an estimate for the non-enumerated population of Rakhine State, which is assumed to mainly affiliate with the Islamic faith; as of December 2019, Muslims probably make up less than 3% of Burma's total population due to the large outmigration of the Rohingya population since 2017

Languages

Burmese (official)

major-language sample(s):

ကမ္ဘာ့အချက်အလက်စာအုပ်- အခြေခံအချက်အလက်တွေအတွက် မရှိမဖြစ်တဲ့ အရင်းအမြစ် (Burmese)

The World Factbook, the indispensable source for basic information.

note: minority ethnic groups use their own languages

major-language sample(s):

ကမ္ဘာ့အချက်အလက်စာအုပ်- အခြေခံအချက်အလက်တွေအတွက် မရှိမဖြစ်တဲ့ အရင်းအမြစ် (Burmese)

The World Factbook, the indispensable source for basic information.

note: minority ethnic groups use their own languages

Burmese audio sample

Imports - partners

China 40%, Thailand 18%, Singapore 15%, Indonesia 4%, Malaysia 4% (2023)

note: top five import partners based on percentage share of imports

note: top five import partners based on percentage share of imports

Elevation

highest point: Gamlang Razi 5,870 m

lowest point: Andaman Sea/Bay of Bengal 0 m

mean elevation: 702 m

lowest point: Andaman Sea/Bay of Bengal 0 m

mean elevation: 702 m

Health expenditure

5.6% of GDP (2021)

2.5% of national budget (2022 est.)

2.5% of national budget (2022 est.)

Military and security service personnel strengths

information varies; estimated 150,000 active military personnel (2025)

note: the Tatmadaw has reportedly suffered heavy personnel losses in the ongoing fighting against anti-regime forces

note: the Tatmadaw has reportedly suffered heavy personnel losses in the ongoing fighting against anti-regime forces

Total water withdrawal

municipal: 3.323 billion cubic meters (2022 est.)

industrial: 498.4 million cubic meters (2022 est.)

agricultural: 29.57 billion cubic meters (2022 est.)

industrial: 498.4 million cubic meters (2022 est.)

agricultural: 29.57 billion cubic meters (2022 est.)

Waste and recycling

municipal solid waste generated annually: 4.677 million tons (2024 est.)

percent of municipal solid waste recycled: 12.3% (2022 est.)

percent of municipal solid waste recycled: 12.3% (2022 est.)

Average household expenditures

on food: 53.9% of household expenditures (2023 est.)

on alcohol and tobacco: 0.5% of household expenditures (2023 est.)

on alcohol and tobacco: 0.5% of household expenditures (2023 est.)

Major watersheds (area sq km)

Indian Ocean drainage: Brahmaputra (651,335 sq km), Ganges (1,016,124 sq km), Irrawaddy (413,710 sq km), Salween (271,914 sq km)

Pacific Ocean drainage: Mekong (805,604 sq km)

Pacific Ocean drainage: Mekong (805,604 sq km)

Major rivers (by length in km)

Mekong (shared with China [s], Laos, Thailand, Cambodia, and Vietnam [m]) - 4,350 km; Salween river mouth (shared with China [s] and Thailand) - 3,060 km; Irrawaddy river mouth (shared with China [s]) - 2,809 km; Chindwin - 1,158 km

note: [s] after country name indicates river source; [m] after country name indicates river mouth

note: [s] after country name indicates river source; [m] after country name indicates river mouth

National heritage

total World Heritage Sites: 2 (both cultural)

selected World Heritage Site locales: Pyu Ancient Cities; Bagan

selected World Heritage Site locales: Pyu Ancient Cities; Bagan

Child marriage

women married by age 15: 1.9% (2016)

women married by age 18: 16% (2016)

men married by age 18: 5% (2016)

women married by age 18: 16% (2016)

men married by age 18: 5% (2016)

Coal

production: 1.031 million metric tons (2023 est.)

consumption: 907,000 metric tons (2023 est.)

exports: 221,000 metric tons (2023 est.)

imports: 67,000 metric tons (2023 est.)

proven reserves: 252 million metric tons (2023 est.)

consumption: 907,000 metric tons (2023 est.)

exports: 221,000 metric tons (2023 est.)

imports: 67,000 metric tons (2023 est.)

proven reserves: 252 million metric tons (2023 est.)

Electricity generation sources

fossil fuels: 61.8% of total installed capacity (2023 est.)

solar: 0.4% of total installed capacity (2023 est.)

hydroelectricity: 36.7% of total installed capacity (2023 est.)

biomass and waste: 1% of total installed capacity (2023 est.)

solar: 0.4% of total installed capacity (2023 est.)

hydroelectricity: 36.7% of total installed capacity (2023 est.)

biomass and waste: 1% of total installed capacity (2023 est.)

Natural gas

production: 13.549 billion cubic meters (2023 est.)

consumption: 4.241 billion cubic meters (2023 est.)

exports: 9.29 billion cubic meters (2023 est.)

imports: 219.822 million cubic meters (2021 est.)

proven reserves: 637.129 billion cubic meters (2021 est.)

consumption: 4.241 billion cubic meters (2023 est.)

exports: 9.29 billion cubic meters (2023 est.)

imports: 219.822 million cubic meters (2021 est.)

proven reserves: 637.129 billion cubic meters (2021 est.)

Petroleum

total petroleum production: 7,000 bbl/day (2023 est.)

refined petroleum consumption: 122,000 bbl/day (2023 est.)

crude oil estimated reserves: 139 million barrels (2021 est.)

refined petroleum consumption: 122,000 bbl/day (2023 est.)

crude oil estimated reserves: 139 million barrels (2021 est.)

Currently married women (ages 15-49)

58% (2019 est.)

Remittances

1.6% of GDP (2023 est.)

2% of GDP (2022 est.)

1.9% of GDP (2021 est.)

note: personal transfers and compensation between resident and non-resident individuals/households/entities

2% of GDP (2022 est.)

1.9% of GDP (2021 est.)

note: personal transfers and compensation between resident and non-resident individuals/households/entities

Ports

total ports: 7 (2024)

large: 0

medium: 0

small: 5

very small: 2

ports with oil terminals: 3

key ports: Bassein, Mergui, Moulmein Harbor, Rangoon, Sittwe

large: 0

medium: 0

small: 5

very small: 2

ports with oil terminals: 3

key ports: Bassein, Mergui, Moulmein Harbor, Rangoon, Sittwe

National color(s)

yellow, green, red, white

Particulate matter emissions

27.2 micrograms per cubic meter (2019 est.)

Labor force

22.742 million (2024 est.)

note: number of people ages 15 or older who are employed or seeking work

note: number of people ages 15 or older who are employed or seeking work

Youth unemployment rate (ages 15-24)

total: 10% (2024 est.)

male: 10.5% (2024 est.)

female: 9.4% (2024 est.)

note: % of labor force ages 15-24 seeking employment

male: 10.5% (2024 est.)

female: 9.4% (2024 est.)

note: % of labor force ages 15-24 seeking employment

Debt - external

$8.748 billion (2023 est.)

note: present value of external debt in current US dollars

note: present value of external debt in current US dollars

Maternal mortality ratio

185 deaths/100,000 live births (2023 est.)

Reserves of foreign exchange and gold

$9.338 billion (2023 est.)

$8.182 billion (2022 est.)

$9.103 billion (2021 est.)

note: holdings of gold (year-end prices)/foreign exchange/special drawing rights in current dollars

$8.182 billion (2022 est.)

$9.103 billion (2021 est.)

note: holdings of gold (year-end prices)/foreign exchange/special drawing rights in current dollars

Unemployment rate

3.1% (2024 est.)

3.1% (2023 est.)

3.1% (2022 est.)

note: % of labor force seeking employment

3.1% (2023 est.)

3.1% (2022 est.)

note: % of labor force seeking employment

Population

total: 57,527,139 (2024 est.)

male: 28,387,831

female: 29,139,308

male: 28,387,831

female: 29,139,308

Carbon dioxide emissions

27.005 million metric tonnes of CO2 (2023 est.)

from coal and metallurgical coke: 1.24 million metric tonnes of CO2 (2023 est.)

from petroleum and other liquids: 17.39 million metric tonnes of CO2 (2023 est.)

from consumed natural gas: 8.376 million metric tonnes of CO2 (2023 est.)

from coal and metallurgical coke: 1.24 million metric tonnes of CO2 (2023 est.)

from petroleum and other liquids: 17.39 million metric tonnes of CO2 (2023 est.)

from consumed natural gas: 8.376 million metric tonnes of CO2 (2023 est.)

Area

total : 676,578 sq km

land: 653,508 sq km

water: 23,070 sq km

land: 653,508 sq km

water: 23,070 sq km

Taxes and other revenues

6% (of GDP) (2019 est.)

note: central government tax revenue as a % of GDP

note: central government tax revenue as a % of GDP

Real GDP (purchasing power parity)

$287.559 billion (2024 est.)

$290.381 billion (2023 est.)

$287.624 billion (2022 est.)

note: data in 2021 dollars

$290.381 billion (2023 est.)

$287.624 billion (2022 est.)

note: data in 2021 dollars

Airports

74 (2025)

Telephones - mobile cellular

total subscriptions: 65.5 million (2023 est.)

subscriptions per 100 inhabitants: 107 (2022 est.)

subscriptions per 100 inhabitants: 107 (2022 est.)

Gini Index coefficient - distribution of family income

30.7 (2017 est.)

note: index (0-100) of income distribution; higher values represent greater inequality

note: index (0-100) of income distribution; higher values represent greater inequality

Inflation rate (consumer prices)

8.8% (2019 est.)

6.9% (2018 est.)

4.6% (2017 est.)

note: annual % change based on consumer prices

6.9% (2018 est.)

4.6% (2017 est.)

note: annual % change based on consumer prices

Current account balance

$67.72 million (2019 est.)

-$2.561 billion (2018 est.)

-$4.917 billion (2017 est.)

note: balance of payments - net trade and primary/secondary income in current dollars

-$2.561 billion (2018 est.)

-$4.917 billion (2017 est.)

note: balance of payments - net trade and primary/secondary income in current dollars

Real GDP per capita

$5,300 (2024 est.)

$5,400 (2023 est.)

$5,400 (2022 est.)

note: data in 2021 dollars

$5,400 (2023 est.)

$5,400 (2022 est.)

note: data in 2021 dollars

Broadband - fixed subscriptions

total: 1.51 million (2023 est.)

subscriptions per 100 inhabitants: 3 (2023 est.)

subscriptions per 100 inhabitants: 3 (2023 est.)

Tobacco use

total: 42.2% (2025 est.)

male: 68.1% (2025 est.)

female: 17.1% (2025 est.)

male: 68.1% (2025 est.)

female: 17.1% (2025 est.)

Obesity - adult prevalence rate

5.8% (2016)

Energy consumption per capita

8.384 million Btu/person (2023 est.)

Electricity

installed generating capacity: 7.419 million kW (2023 est.)

consumption: 23.625 billion kWh (2023 est.)

exports: 200 million kWh (2023 est.)

transmission/distribution losses: 1.855 billion kWh (2023 est.)

consumption: 23.625 billion kWh (2023 est.)

exports: 200 million kWh (2023 est.)

transmission/distribution losses: 1.855 billion kWh (2023 est.)

Merchant marine

total: 101 (2023)

by type: bulk carrier 1, general cargo 44, oil tanker 5, other 51

by type: bulk carrier 1, general cargo 44, oil tanker 5, other 51

Children under the age of 5 years underweight

19.5% (2018 est.)

Imports

$23.1 billion (2021 est.)

$17.356 billion (2019 est.)

$18.664 billion (2018 est.)

note: balance of payments - imports of goods and services in current dollars

$17.356 billion (2019 est.)

$18.664 billion (2018 est.)

note: balance of payments - imports of goods and services in current dollars

Exports

$20.4 billion (2021 est.)

$17.523 billion (2019 est.)

$15.728 billion (2018 est.)

note: balance of payments - exports of goods and services in current dollars

$17.523 billion (2019 est.)

$15.728 billion (2018 est.)

note: balance of payments - exports of goods and services in current dollars

Heliports

6 (2025)

Telephones - fixed lines

total subscriptions: 588,000 (2023 est.)

subscriptions per 100 inhabitants: 1 (2023 est.) less than 1

subscriptions per 100 inhabitants: 1 (2023 est.) less than 1

Alcohol consumption per capita

total: 2.06 liters of pure alcohol (2019 est.)

beer: 0.5 liters of pure alcohol (2019 est.)

wine: 0.02 liters of pure alcohol (2019 est.)

spirits: 1.55 liters of pure alcohol (2019 est.)

other alcohols: 0 liters of pure alcohol (2019 est.)

beer: 0.5 liters of pure alcohol (2019 est.)

wine: 0.02 liters of pure alcohol (2019 est.)

spirits: 1.55 liters of pure alcohol (2019 est.)

other alcohols: 0 liters of pure alcohol (2019 est.)

Life expectancy at birth

total population: 70.3 years (2024 est.)

male: 68.5 years

female: 72.1 years

male: 68.5 years

female: 72.1 years

Real GDP growth rate

-1% (2024 est.)

1% (2023 est.)

4% (2022 est.)

note: annual GDP % growth based on constant local currency

1% (2023 est.)

4% (2022 est.)

note: annual GDP % growth based on constant local currency

Industrial production growth rate

-0.2% (2024 est.)

note: annual % change in industrial value added based on constant local currency

note: annual % change in industrial value added based on constant local currency

GDP - composition, by sector of origin

agriculture: 20.8% (2024 est.)

industry: 37.8% (2024 est.)

services: 41.4% (2024 est.)

note: figures may not total 100% due to non-allocated consumption not captured in sector-reported data

industry: 37.8% (2024 est.)

services: 41.4% (2024 est.)

note: figures may not total 100% due to non-allocated consumption not captured in sector-reported data

Education expenditure

2% of GDP (2019 est.)

9.7% national budget (2019 est.)

9.7% national budget (2019 est.)

Military - note

since the country’s founding, the Tatmadaw has been deeply involved in domestic politics and the national economy; it ran the country for five decades following a military coup in 1962; prior to the most recent coup in 2021, the military already controlled three key security ministries (Defense, Border, and Home Affairs), one of two vice presidential appointments, 25% of the parliamentary seats, and had a proxy political party, the Union Solidarity and Development Party (USDP); it owns and operates two business conglomerates that have over 100 subsidiaries; the business activities of these conglomerates include banking and insurance, hotels, tourism, jade and ruby mining, timber, construction, real estate, and the production of palm oil, sugar, soap, cement, beverages, drinking water, coal, and gas; some of the companies supply goods and services to the military, such as food, clothing, insurance, and cellphone service; the military also manages a film industry, publishing houses, and television stations

the Tatmadaw's primary operational focus is internal security, and it is conducting counterinsurgency operations against anti-regime forces that launched an armed rebellion following the 2021 coup and an array of ethnic armed groups (EAGs); as of 2024, the Tatmadaw was reportedly engaged in combat operations in 10 of its 14 regional commands

EAGs have been fighting for self-rule against the Burmese Government since 1948; they range in strength from a few hundred fighters up to an estimated 30,000; some are organized along military lines with "brigades" and "divisions" and armed with heavy weaponry, including artillery; they control large tracts of the country’s territory, primarily in the border regions; key groups include the United Wa State Army, Karen National Union, Kachin Independence Army, Arakan Army, Ta’ang National Liberation Army, and the Myanmar Nationalities Democratic Alliance Army

the opposition National Unity Government claims its armed wing, the People's Defense Force (PDF), has more than 60,000 fighters loosely organized into battalions; in addition, several EAGs have cooperated with the NUG and supported local PDF groups (2024)

the Tatmadaw's primary operational focus is internal security, and it is conducting counterinsurgency operations against anti-regime forces that launched an armed rebellion following the 2021 coup and an array of ethnic armed groups (EAGs); as of 2024, the Tatmadaw was reportedly engaged in combat operations in 10 of its 14 regional commands

EAGs have been fighting for self-rule against the Burmese Government since 1948; they range in strength from a few hundred fighters up to an estimated 30,000; some are organized along military lines with "brigades" and "divisions" and armed with heavy weaponry, including artillery; they control large tracts of the country’s territory, primarily in the border regions; key groups include the United Wa State Army, Karen National Union, Kachin Independence Army, Arakan Army, Ta’ang National Liberation Army, and the Myanmar Nationalities Democratic Alliance Army

the opposition National Unity Government claims its armed wing, the People's Defense Force (PDF), has more than 60,000 fighters loosely organized into battalions; in addition, several EAGs have cooperated with the NUG and supported local PDF groups (2024)

Military service age and obligation

18-35 years of age (men) and 18-27 years of age (women) for voluntary and conscripted military service; 24-month service obligation; conscripted professional men (ages 18-45) and women (ages 18-35), including doctors, engineers, and mechanics, serve up to 36 months; service terms may be extended to 60 months in an officially declared emergency (2025)

note: in February 2024, the military government announced that the People’s Military Service Law requiring mandatory military service would go into effect; the Service Law was first introduced in 2010 but had not previously been enforced; the military government also said that it intended to call up about 60,000 men and women annually for mandatory service; during the ongoing insurgency, the military has recruited men 18-60 to serve in local militias

note: in February 2024, the military government announced that the People’s Military Service Law requiring mandatory military service would go into effect; the Service Law was first introduced in 2010 but had not previously been enforced; the military government also said that it intended to call up about 60,000 men and women annually for mandatory service; during the ongoing insurgency, the military has recruited men 18-60 to serve in local militias

Legislative branch

legislature name: Assembly of the Union (Pyidaungsu Hluttaw)

legislative structure: bicameral

most recent election date: 28 December 2025

expected date of next election: on 31 July 2025, the military government announced that it was preparing for elections to be held in late December 2025

note: on 1 February 2021, the Burmese military claimed the results of the 2020 general election were illegitimate and launched a coup led by Sr. General MIN AUNG HLAING; the military subsequently dissolved the Assembly of the Union and replaced it with the military-led State Administration Council

legislative structure: bicameral

most recent election date: 28 December 2025

expected date of next election: on 31 July 2025, the military government announced that it was preparing for elections to be held in late December 2025

note: on 1 February 2021, the Burmese military claimed the results of the 2020 general election were illegitimate and launched a coup led by Sr. General MIN AUNG HLAING; the military subsequently dissolved the Assembly of the Union and replaced it with the military-led State Administration Council

Political parties

according to the military regime, more than 50 parties registered and were approved for the December 2025 election, but only 9 contested nationwide; the remainder ran in regional or state constituencies

the 9 parties included:

Democratic Party of National Politics (DNP)

Myanmar Farmers Development Party (MFDP)

National Democratic Force Party (NDF)

National Unity Party (NUP)

People’s Party

People’s Pioneer Party (PPP)

Shan and Ethnic Democratic Party (SEDP)

Union Solidarity and Development Party (USDP)

Women’s Party (Mon)

note: more than 90 political parties participated in the 2020 elections; political parties continued to function after the 2021 coup, although some political leaders have been arrested by the military regime; in 2023, the regime announced a new law with several rules and restrictions on political parties and their ability to participate in elections; dozens of parties refused to comply with the new rules; the regime's election commission has subsequently banned more than 80 political parties, including the National League for Democracy

the 9 parties included:

Democratic Party of National Politics (DNP)

Myanmar Farmers Development Party (MFDP)

National Democratic Force Party (NDF)

National Unity Party (NUP)

People’s Party

People’s Pioneer Party (PPP)

Shan and Ethnic Democratic Party (SEDP)

Union Solidarity and Development Party (USDP)

Women’s Party (Mon)

note: more than 90 political parties participated in the 2020 elections; political parties continued to function after the 2021 coup, although some political leaders have been arrested by the military regime; in 2023, the regime announced a new law with several rules and restrictions on political parties and their ability to participate in elections; dozens of parties refused to comply with the new rules; the regime's election commission has subsequently banned more than 80 political parties, including the National League for Democracy

Military equipment inventories and acquisitions

the Burmese military's inventory is comprised of mostly Chinese, Russian, or Soviet-era armaments; Burma's defense industry is involved in shipbuilding and the production of ground force equipment based largely on Chinese and Russian designs (2025)

Gross reproduction rate

0.95 (2025 est.)

Net migration rate

-1.36 migrant(s)/1,000 population (2025 est.)

Median age

total: 31.1 years (2025 est.)

male: 29.9 years

female: 31.6 years

male: 29.9 years

female: 31.6 years

Total fertility rate

1.95 children born/woman (2025 est.)

Infant mortality rate

total: 30.8 deaths/1,000 live births (2025 est.)

male: 35.4 deaths/1,000 live births

female: 28.5 deaths/1,000 live births

male: 35.4 deaths/1,000 live births

female: 28.5 deaths/1,000 live births

Death rate

7.17 deaths/1,000 population (2025 est.)

Birth rate

15.44 births/1,000 population (2025 est.)

Population growth rate

0.69% (2025 est.)